Whatever

Happened to Republican Feminists?

by Jo Freeman (1996)

For

most of this country's history the Republican Party provided a much

warmer reception to women, and in particular those women actively

working to promote women's rights, than did the Democratic Party.

Traditionally, the Republican Party was the more feminist of the major

political parties.

For

most of this country's history the Republican Party provided a much

warmer reception to women, and in particular those women actively

working to promote women's rights, than did the Democratic Party.

Traditionally, the Republican Party was the more feminist of the major

political parties.

Between

1970 and 1973 the parties switched sides; since then they have been

rapidly going in the opposite directions in their attitudes towards

women's rights and their programs to improve women's situation.

Between

1970 and 1973 the parties switched sides; since then they have been

rapidly going in the opposite directions in their attitudes towards

women's rights and their programs to improve women's situation.

A

brief look at history illuminates the profundity of this switch. Most

of the women who first demanded suffrage in 1848 were involved in

the antislavery movement and vigorously supported the party which

freed the slaves.

A

brief look at history illuminates the profundity of this switch. Most

of the women who first demanded suffrage in 1848 were involved in

the antislavery movement and vigorously supported the party which

freed the slaves.

Suffragists

were particularly active on behalf of President Grant's re-election

in 1872, William McKinley's campaign against William Jennings Bryan

in 1896, and Theodore Roosevelt's campaign against Taft and Wilson

in 1912.

Suffragists

were particularly active on behalf of President Grant's re-election

in 1872, William McKinley's campaign against William Jennings Bryan

in 1896, and Theodore Roosevelt's campaign against Taft and Wilson

in 1912.

J. Ellen Foster

J. Ellen Foster

|

The

Republican Party saw the importance of women to winning elections

even in states where women could not vote. In 1888 the Republican

National Committee asked J. Ellen Foster, an attorney and temperance

worker from Iowa, to organize the National Woman's Republican Association.

While the Populists, the Prohibitionists and other small parties also

organized women to work for their candidates, the Democrats did little.

It was 1912 before there was a Women's National Democratic League,

and it was composed mostly of the wives of Members of Congress.

In

the 1890s women took up the job of municipal reform. In New York the

West End Women's Republican Association worked to defeat Tammany Hall,

while the Democratic newspaper asked "Where are the Democratic

Women?" In 1894 and 1896 the Illinois Republican Women's State

Central Committee sent Ida Wells-Barnett, prominent African-American

journalist, on a lecture tour around the state on behalf of Republican

candidates. In California the Republican Party, but not the Democrats,

supported women candidates for local school boards and for suffrage.

In

the 1890s women took up the job of municipal reform. In New York the

West End Women's Republican Association worked to defeat Tammany Hall,

while the Democratic newspaper asked "Where are the Democratic

Women?" In 1894 and 1896 the Illinois Republican Women's State

Central Committee sent Ida Wells-Barnett, prominent African-American

journalist, on a lecture tour around the state on behalf of Republican

candidates. In California the Republican Party, but not the Democrats,

supported women candidates for local school boards and for suffrage.

In

1916 militant suffragists formed the National Woman's Party to campaign

against all Democrats in the twelve states where women could vote

for President to punish them for failure to support woman suffrage.

While neither Party supported a federal suffrage amendment in its platform, Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes endorsed one on

August 1, 1916. President Wilson didn't do so until 1918. The women

who had supported Roosevelt in 1912 formed the Women's Committee of

the Hughes Alliance and raised over $132,000 from 1,100 contributors

for their own campaign. They organized and financed a special train

to travel throughout the suffrage states holding rallies where women

orators mobilized supporters.

In

1916 militant suffragists formed the National Woman's Party to campaign

against all Democrats in the twelve states where women could vote

for President to punish them for failure to support woman suffrage.

While neither Party supported a federal suffrage amendment in its platform, Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes endorsed one on

August 1, 1916. President Wilson didn't do so until 1918. The women

who had supported Roosevelt in 1912 formed the Women's Committee of

the Hughes Alliance and raised over $132,000 from 1,100 contributors

for their own campaign. They organized and financed a special train

to travel throughout the suffrage states holding rallies where women

orators mobilized supporters.

Before

the days of exit polls it is hard to tell exactly how women voted,

but the few analyses that have been done indicate that there was a

gender gap in favor of the Republican Party in most places at least

until the 1930s. Indeed in the elections of 1952 and 1956 women were

six percent more likely to vote for Republican Eisenhower than men

were.

Before

the days of exit polls it is hard to tell exactly how women voted,

but the few analyses that have been done indicate that there was a

gender gap in favor of the Republican Party in most places at least

until the 1930s. Indeed in the elections of 1952 and 1956 women were

six percent more likely to vote for Republican Eisenhower than men

were.

Women

were particularly active on behalf of Herbert Hoover in 1928. The

NWP endorsed him. Moderate suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt campaigned

for him. Hoover got as much as 65 percent of the women's vote.

Women

were particularly active on behalf of Herbert Hoover in 1928. The

NWP endorsed him. Moderate suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt campaigned

for him. Hoover got as much as 65 percent of the women's vote.

In

the 1920s thousands of Republican Women's Clubs were organized throughout

the country. The National Federation of Republican Women was founded

in 1938 and today is one of the largest women's organizations. While

the Democrats made a major effort to organize women during FDR's first

two terms, this faded after 1940.

In

the 1920s thousands of Republican Women's Clubs were organized throughout

the country. The National Federation of Republican Women was founded

in 1938 and today is one of the largest women's organizations. While

the Democrats made a major effort to organize women during FDR's first

two terms, this faded after 1940.

In

1940 the RNC adopted rules requiring equal representation of women

on all RNC Committees. Equal representation on the convention platform

committee became the rule in 1944, and on all convention committees

in 1960.

In

1940 the RNC adopted rules requiring equal representation of women

on all RNC Committees. Equal representation on the convention platform

committee became the rule in 1944, and on all convention committees

in 1960.

Through

1968 women had more space in the Republican Party platform and usually

had proportionately more delegates at its national convention than

did the Democrats.

Through

1968 women had more space in the Republican Party platform and usually

had proportionately more delegates at its national convention than

did the Democrats.

The

GOP endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment four years earlier than the

Democrats -- in 1940 -- and took it out four years later -- in 1964.

The first three Presidents to support the Equal Rights Amendment were

Republicans -- Eisenhower, Nixon and Ford.

The

GOP endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment four years earlier than the

Democrats -- in 1940 -- and took it out four years later -- in 1964.

The first three Presidents to support the Equal Rights Amendment were

Republicans -- Eisenhower, Nixon and Ford.

During

the 1970-72 campaign for Congressional passage of the ERA two of the

most active supporters were the President of the National Federation

of Republican Women and the female co-chair of the Republican National

Committee.

During

the 1970-72 campaign for Congressional passage of the ERA two of the

most active supporters were the President of the National Federation

of Republican Women and the female co-chair of the Republican National

Committee.

By

1980 all this had changed.

By

1980 all this had changed.

Mary Crisp

Mary Crisp

|

At

their convention that year the Republican Party removed the ERA from

its platform a second time -- only eight years after both parties

resumed support. It actively opposed legalized abortion and generally

shunned those few Republican women still willing to call themselves

feminists. Co-chair Mary Crisp, an ERA activist who had campaigned

for Goldwater in 1964, was virtually read out of the party.

That

November a "gender gap" in Presidential voting appeared,

with women voting more Democratic than men. Since then Republican

Members of Congress have voted increasingly against bills supported

by feminist groups, and women have voted increasingly for Democrats

over Republicans. Even when the 1984 Reagan campaign specifically

targeted women, the gender gap remained. Indeed, it spread from the

Presidential to many state and local races.

That

November a "gender gap" in Presidential voting appeared,

with women voting more Democratic than men. Since then Republican

Members of Congress have voted increasingly against bills supported

by feminist groups, and women have voted increasingly for Democrats

over Republicans. Even when the 1984 Reagan campaign specifically

targeted women, the gender gap remained. Indeed, it spread from the

Presidential to many state and local races.

By

Spring 1996, surveys showed that sixteen percent more men identified

with the Republican Party than the Democrats, while eight per cent

more women said they were Democrats than Republicans. Even among African

Americans women were five to ten percent more likely to be Democrats

than men were. In the 1996 Presidential race, the gender gap was eleven

percent overall and 17 percent among those under 30. It spread to

many other races.

By

Spring 1996, surveys showed that sixteen percent more men identified

with the Republican Party than the Democrats, while eight per cent

more women said they were Democrats than Republicans. Even among African

Americans women were five to ten percent more likely to be Democrats

than men were. In the 1996 Presidential race, the gender gap was eleven

percent overall and 17 percent among those under 30. It spread to

many other races.

What

happened?

What

happened?

Although

the feminist movement wanted to be bipartisan and organized women

within both major parties, these efforts were not equally successful.

In the Democratic Party women formed alliances with those who wanted

to make their party more inclusive. In the Republican Party feminists

were swimming against the tide.

Although

the feminist movement wanted to be bipartisan and organized women

within both major parties, these efforts were not equally successful.

In the Democratic Party women formed alliances with those who wanted

to make their party more inclusive. In the Republican Party feminists

were swimming against the tide.

That

tide was the New Right, which had been trying to take over the Republican

Party since Goldwater's campaign in 1964. In the early 1970s it had

no particular interest in women; some New Rightists were pro ERA and

pro Choice.

That

tide was the New Right, which had been trying to take over the Republican

Party since Goldwater's campaign in 1964. In the early 1970s it had

no particular interest in women; some New Rightists were pro ERA and

pro Choice.

But

the New Right saw victory in an alliance with social conservatives

who traditionally voted Democratic, and in particular with Southerners

who did not like racial integration and the greater intrusion of government

that it led to. It wanted to leverage the backlash against social

change into a Republican vote. The New Right first recruited fundamentalist

ministers, especially in the South, who had stayed out of politics

for decades because they thought it was dirty. The ministers were

persuaded that the country's culture was being corrupted by the militant

secularists, who had captured the Democratic Party. They convinced

many of their flocks that it was the duty of all good Christians to

involve themselves in politics in order to take back their culture

and their institutions.

But

the New Right saw victory in an alliance with social conservatives

who traditionally voted Democratic, and in particular with Southerners

who did not like racial integration and the greater intrusion of government

that it led to. It wanted to leverage the backlash against social

change into a Republican vote. The New Right first recruited fundamentalist

ministers, especially in the South, who had stayed out of politics

for decades because they thought it was dirty. The ministers were

persuaded that the country's culture was being corrupted by the militant

secularists, who had captured the Democratic Party. They convinced

many of their flocks that it was the duty of all good Christians to

involve themselves in politics in order to take back their culture

and their institutions.

Legalized

abortion expanded the backlash. When the Catholic Church mobilized

opposition to abortion, New Right leaders saw a golden opportunity

to go fishing among Catholics. Sex was added to race as a highly charged

emotional issue which could uncouple traditional Democratic voters

from the party of their birth. Indeed sex was a much better issue

than race to rouse voters out of their disenchantment with politics.

Racism was vaguely immoral; it had to be disguised as big bad government

to be palatable. Sex was more suspect. Republicans labeled feminism

as immoral sexuality -- i.e. abortion, homosexuality, mothering without

marriage -- and touted themselves as the party of "family values."

Legalized

abortion expanded the backlash. When the Catholic Church mobilized

opposition to abortion, New Right leaders saw a golden opportunity

to go fishing among Catholics. Sex was added to race as a highly charged

emotional issue which could uncouple traditional Democratic voters

from the party of their birth. Indeed sex was a much better issue

than race to rouse voters out of their disenchantment with politics.

Racism was vaguely immoral; it had to be disguised as big bad government

to be palatable. Sex was more suspect. Republicans labeled feminism

as immoral sexuality -- i.e. abortion, homosexuality, mothering without

marriage -- and touted themselves as the party of "family values."

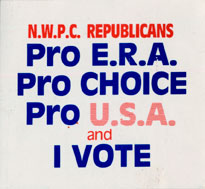

By

playing on the fears of change raised by feminism and the vastly changing

role of women in our society, the New Right has created a new and

potent partisan cleavage in the electorate, one which, like race,

is gradually realigning major voting blocs. It has also created a

fracture -- albeit a small one -- within the Republican Party. This

fracture centers around abortion, but in fact involves broader concerns

of sex, sexuality and the role of women. Republicans who called themselves

feminists twenty years ago now organize as "pro-choice Republicans".

Unfortunately, they are better at publicizing their concerns than

at organizing the grass roots, so it is unlikely that they will be

more than an irritant to the Republican party for many, many years.

By

playing on the fears of change raised by feminism and the vastly changing

role of women in our society, the New Right has created a new and

potent partisan cleavage in the electorate, one which, like race,

is gradually realigning major voting blocs. It has also created a

fracture -- albeit a small one -- within the Republican Party. This

fracture centers around abortion, but in fact involves broader concerns

of sex, sexuality and the role of women. Republicans who called themselves

feminists twenty years ago now organize as "pro-choice Republicans".

Unfortunately, they are better at publicizing their concerns than

at organizing the grass roots, so it is unlikely that they will be

more than an irritant to the Republican party for many, many years.

In

the last 25 years, the two major parties have undergone a realignment,

on at least on one cluster of issues. They are now polarized around

feminism and the reaction to it, with different programs and different

visions of how to deal with sex and the role of women. The Republicans

are now the party of traditional family values, while Democrats are

following the feminist agenda of making the personal, political. Republican

feminists are left with an onerous choice: they can stay in the party

and suppress their feminist concerns, or they can leave.

In

the last 25 years, the two major parties have undergone a realignment,

on at least on one cluster of issues. They are now polarized around

feminism and the reaction to it, with different programs and different

visions of how to deal with sex and the role of women. The Republicans

are now the party of traditional family values, while Democrats are

following the feminist agenda of making the personal, political. Republican

feminists are left with an onerous choice: they can stay in the party

and suppress their feminist concerns, or they can leave.