WOMEN

AT THE 1988 DEMOCRATIC CONVENTION

by Jo Freeman

Published

in off our backs, October 1988, pp. 4-5.

![]() The

activities of feminist and other women's organizations at the 1988

Democratic convention were driven by an overriding desire to elect

a Democratic administration in November. There was universal agreement

that the Reagan years have been disastrous for women, and that four

more years of Republican rule will, at the very least, result in a

Supreme Court that will limit women's options for decades to come.

The

activities of feminist and other women's organizations at the 1988

Democratic convention were driven by an overriding desire to elect

a Democratic administration in November. There was universal agreement

that the Reagan years have been disastrous for women, and that four

more years of Republican rule will, at the very least, result in a

Supreme Court that will limit women's options for decades to come.

![]() This

goal more than anything else explains the relative quiescence of the

fifteen organizations1 that formed

Women's Central and held the usual women's caucus every day of the

convention. Indeed when Ellie Smeal and Molly Yard, past and current

Presidents of NOW, expressed some mild disaffection with the amount

of attention feminist issues and representatives received from the

Dukakis campaign, it was quickly countered with a press conference

by heads of six Women's Central organizations to extol the fact that

women were now insiders. And Kate Michelman, executive director of

NARAL, lauded Vice-Presidential candidate Lloyd Bentsen's voting record

on abortion even though he opposes federal funding.

This

goal more than anything else explains the relative quiescence of the

fifteen organizations1 that formed

Women's Central and held the usual women's caucus every day of the

convention. Indeed when Ellie Smeal and Molly Yard, past and current

Presidents of NOW, expressed some mild disaffection with the amount

of attention feminist issues and representatives received from the

Dukakis campaign, it was quickly countered with a press conference

by heads of six Women's Central organizations to extol the fact that

women were now insiders. And Kate Michelman, executive director of

NARAL, lauded Vice-Presidential candidate Lloyd Bentsen's voting record

on abortion even though he opposes federal funding.

![]() The

sense of unity and common purpose these women expressed was not artificial,

because to a greater extent than ever thought possible when contemporary

feminists first made demands at the 1972 convention, women were

insiders. The Dukakis campaign emphasized that women held a large

numbers of the top positions -- including campaign manager Susan Estrich.

Texas Treasurer Ann Richards, a member of the NWPC, was a big hit

as the keynote speaker. And even Ellie Smeal agreed that the Platform

contained everything feminists had demanded.

The

sense of unity and common purpose these women expressed was not artificial,

because to a greater extent than ever thought possible when contemporary

feminists first made demands at the 1972 convention, women were

insiders. The Dukakis campaign emphasized that women held a large

numbers of the top positions -- including campaign manager Susan Estrich.

Texas Treasurer Ann Richards, a member of the NWPC, was a big hit

as the keynote speaker. And even Ellie Smeal agreed that the Platform

contained everything feminists had demanded.

![]() Fights

over platform language have provided a unifying agenda for feminists

at past conventions, particularly in 1980 when the Carter campaign

unsuccessfully opposed a feminist plank to deny Democratic Party funds

to any candidate who did not support the ERA. However, in 1984 the

Mondale campaign sought the endorsement of NOW early on, and ceded

"sign off" authority on all platform language concerning

women to Mary Jean Collins, NOW's Action Vice President that year.

No single person or organization had that authority in 1988. Instead,

a coalition of groups worked with Eleanor Holmes Norton of the Jackson

campaign and Michael Barnes of Dukakis' campaign to achieve mutually

agreeable language.

Fights

over platform language have provided a unifying agenda for feminists

at past conventions, particularly in 1980 when the Carter campaign

unsuccessfully opposed a feminist plank to deny Democratic Party funds

to any candidate who did not support the ERA. However, in 1984 the

Mondale campaign sought the endorsement of NOW early on, and ceded

"sign off" authority on all platform language concerning

women to Mary Jean Collins, NOW's Action Vice President that year.

No single person or organization had that authority in 1988. Instead,

a coalition of groups worked with Eleanor Holmes Norton of the Jackson

campaign and Michael Barnes of Dukakis' campaign to achieve mutually

agreeable language.

![]() Although

the final result was the same as in 1984, the process was more problematical.

Feminists were alarmed last December when Democratic National Committee

Chair Paul G. Kirk, Jr. stated that he wanted a platform that was

short and softpedaled such controversial issues as abortion and the

ERA. Twenty women leaders met with Kirk to point out that leaving

those issues out would be more controversial at the convention than

putting them in. The group included representatives from NOW, NWPC,

BPW, AAUW, and women such as Rep. Mary Rose Oakar (D. Ohio), and Ann

Lewis, head of the NWPC's Democratic Task Force and former political

director of the DNC.

Although

the final result was the same as in 1984, the process was more problematical.

Feminists were alarmed last December when Democratic National Committee

Chair Paul G. Kirk, Jr. stated that he wanted a platform that was

short and softpedaled such controversial issues as abortion and the

ERA. Twenty women leaders met with Kirk to point out that leaving

those issues out would be more controversial at the convention than

putting them in. The group included representatives from NOW, NWPC,

BPW, AAUW, and women such as Rep. Mary Rose Oakar (D. Ohio), and Ann

Lewis, head of the NWPC's Democratic Task Force and former political

director of the DNC.

![]() Kirk

agreed to meet regularly with a smaller task force chosen by the women

leaders, and Rep. Oakar called two major meetings of feminist, union

and liberal organizations to talk to select platform committee members

about their concerns. After Michigan Gov. James J. Blanchard was named

chair of the platform committee he also met with feminist representatives,

including Irene Natividad of the NWPC, Kate Michelman of NARAL and

Judith Lichtman of the Women's Legal Defense Fund. According to Michelman,

Blanchard was receptive to explicit mention of feminist concerns in

the platform.

Kirk

agreed to meet regularly with a smaller task force chosen by the women

leaders, and Rep. Oakar called two major meetings of feminist, union

and liberal organizations to talk to select platform committee members

about their concerns. After Michigan Gov. James J. Blanchard was named

chair of the platform committee he also met with feminist representatives,

including Irene Natividad of the NWPC, Kate Michelman of NARAL and

Judith Lichtman of the Women's Legal Defense Fund. According to Michelman,

Blanchard was receptive to explicit mention of feminist concerns in

the platform.

![]() Nonetheless, the initial draft of the platform written by Ted Sorenson

at the behest of Kirk did not reflect the understandings of that Spring

when it was presented to the 16 member drafting committee on June

10. Instead of endorsing the ERA and a woman's right to choose abortion,

it made casual reference to "equal rights of all men and women"

and "freedom of choice regarding childbirth."

Nonetheless, the initial draft of the platform written by Ted Sorenson

at the behest of Kirk did not reflect the understandings of that Spring

when it was presented to the 16 member drafting committee on June

10. Instead of endorsing the ERA and a woman's right to choose abortion,

it made casual reference to "equal rights of all men and women"

and "freedom of choice regarding childbirth."

![]() The DNC traditionally defers to the desires of the winning candidates

in writing the platform so Jackson's and Dukakis' representatives,

Norton and Barnes, had the final say. Norton, Chair of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission during the Carter administration and currently

a professor at Georgetown Law School has a long record of supporting

feminist issues. While Barnes, a former Maryland Congressman, lacked

her track record, his instructions were clear. Alice Travis, National

Political Director of the Dukakis campaign had met with Dukakis shortly

after Kirk's December statement and reminded him that it was important

that ERA and abortion be explicitly mentioned in the platform.

The DNC traditionally defers to the desires of the winning candidates

in writing the platform so Jackson's and Dukakis' representatives,

Norton and Barnes, had the final say. Norton, Chair of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission during the Carter administration and currently

a professor at Georgetown Law School has a long record of supporting

feminist issues. While Barnes, a former Maryland Congressman, lacked

her track record, his instructions were clear. Alice Travis, National

Political Director of the Dukakis campaign had met with Dukakis shortly

after Kirk's December statement and reminded him that it was important

that ERA and abortion be explicitly mentioned in the platform.

![]() Representatives of NOW, NWPC, and NARAL met with Norton and Barnes

at the drafting committee meeting. They also worked through five strong

sympathizers on the committee itself. "A lot of the major players

were our folk", Natividad said. While not unhappy with the proposals

that emerged from the June 10 meeting, the women thought there was

room for improvement at the full Platform Committee meeting in Denver

on June 25. According to Michelman, in Denver "the language was

expanded, not by motions and votes but behind the scenes." The

final platform contained "the whole gamut of women's issues,"

she said, though in abbreviated form and not in any one section. Conciseness

was typical of the entire platform, not just feminist concerns.

Representatives of NOW, NWPC, and NARAL met with Norton and Barnes

at the drafting committee meeting. They also worked through five strong

sympathizers on the committee itself. "A lot of the major players

were our folk", Natividad said. While not unhappy with the proposals

that emerged from the June 10 meeting, the women thought there was

room for improvement at the full Platform Committee meeting in Denver

on June 25. According to Michelman, in Denver "the language was

expanded, not by motions and votes but behind the scenes." The

final platform contained "the whole gamut of women's issues,"

she said, though in abbreviated form and not in any one section. Conciseness

was typical of the entire platform, not just feminist concerns.

![]() As

proposed by the Committee and passed in Atlanta by the Democratic

National Convention, the Platform urges adoption of the ERA and demands

that "the fundamental right of reproductive choice should be

guaranteed regardless of ability to pay." It also states that

"we honor our multicultural heritage by assuring equal access

to government services, employment, housing, business enterprise and

education to every citizen regardless of race, sex, national origin,

religion, age, handicapping condition or sexual orientation."

As

proposed by the Committee and passed in Atlanta by the Democratic

National Convention, the Platform urges adoption of the ERA and demands

that "the fundamental right of reproductive choice should be

guaranteed regardless of ability to pay." It also states that

"we honor our multicultural heritage by assuring equal access

to government services, employment, housing, business enterprise and

education to every citizen regardless of race, sex, national origin,

religion, age, handicapping condition or sexual orientation."

![]() In addition to these traditional planks, the Democratic party is on

record in favor of "pay equity for working women" and "family

leave policies that no longer force employees to choose between their

jobs and their children or ailing parents." Child care is mentioned

three times. The section on revitalization of the "country's

democratic processes" contains a NOW proposal supporting "the

full and equal access of women and minorities to elective office and

party endorsement".

In addition to these traditional planks, the Democratic party is on

record in favor of "pay equity for working women" and "family

leave policies that no longer force employees to choose between their

jobs and their children or ailing parents." Child care is mentioned

three times. The section on revitalization of the "country's

democratic processes" contains a NOW proposal supporting "the

full and equal access of women and minorities to elective office and

party endorsement".

Actress Margot Kidder speaks on

behalf of the Jackson planks

![]() Although women got everything they wanted in the Platform, the Jackson

campaign didn't. Ten minority reports were filed (requiring the vote

of one-fourth of the Platform Committee) of which three were chosen

by the Jackson campaign for debate at the convention. Because there

were no burning issues on the feminist agenda at the convention, the

Women's Central organizations allotted the first two days of its caucus

to debate on the Jackson minority proposals. They concerned Palestine,

"no first use" of nuclear weapons and raising taxes. However

most of the several hundred women attending the caucus meetings were

not delegates, and only a few were really interested in those topics.

The debates were very short, and when delegates only were asked to

express their preference for the issues under debate, less than two

dozen members of the audience raised their hands.

Although women got everything they wanted in the Platform, the Jackson

campaign didn't. Ten minority reports were filed (requiring the vote

of one-fourth of the Platform Committee) of which three were chosen

by the Jackson campaign for debate at the convention. Because there

were no burning issues on the feminist agenda at the convention, the

Women's Central organizations allotted the first two days of its caucus

to debate on the Jackson minority proposals. They concerned Palestine,

"no first use" of nuclear weapons and raising taxes. However

most of the several hundred women attending the caucus meetings were

not delegates, and only a few were really interested in those topics.

The debates were very short, and when delegates only were asked to

express their preference for the issues under debate, less than two

dozen members of the audience raised their hands.

![]() Jackson had sought the support of the women's caucus for his planks

in 1984, but few of his supporters were present for the debate in

1988. According to Vicki Alexander, Chair of the Women's Commission

of the Rainbow Coalition and an at-large delegate from New York, the

Jackson delegates "didn't see women as a primary issue and wanted

to work for Jackson in their state delegations."

Jackson had sought the support of the women's caucus for his planks

in 1984, but few of his supporters were present for the debate in

1988. According to Vicki Alexander, Chair of the Women's Commission

of the Rainbow Coalition and an at-large delegate from New York, the

Jackson delegates "didn't see women as a primary issue and wanted

to work for Jackson in their state delegations."

![]() Also absent was the antagonism between black women and the "white

women's movement" that had marked the 1984 convention and resulted

in a separate, closed, caucus of black women. At that time, black

women, most of whom were Jackson supporters, were angry that Mondale

had not interviewed any minority women when searching for a running

mate. According to former Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm

they asked the Women's Coalition to support the Jackson minority planks

with the delegate whip system that had been created to put a woman's

name into nomination if Mondale didn't. She said they were angry when

the Coalition instead dismantled the whip system.

Also absent was the antagonism between black women and the "white

women's movement" that had marked the 1984 convention and resulted

in a separate, closed, caucus of black women. At that time, black

women, most of whom were Jackson supporters, were angry that Mondale

had not interviewed any minority women when searching for a running

mate. According to former Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm

they asked the Women's Coalition to support the Jackson minority planks

with the delegate whip system that had been created to put a woman's

name into nomination if Mondale didn't. She said they were angry when

the Coalition instead dismantled the whip system.

Shirley Chisholm

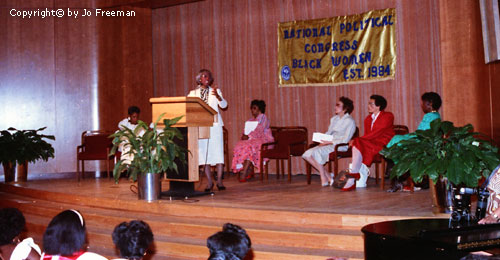

![]() Shortly after the 1984 Democratic Convention, Chisholm, a founder

in 1971 of the National Women's Political Caucus, also founded the

National Political Congress of Black Women. While in Atlanta for the

1988 convention, she convened an Atlanta chapter and inducted over

a hundred local Atlantans into her organization. She urged them to

run for office. "If we do this we won't have to go to the table,"

she told the women. "They will seek us out."

Shortly after the 1984 Democratic Convention, Chisholm, a founder

in 1971 of the National Women's Political Caucus, also founded the

National Political Congress of Black Women. While in Atlanta for the

1988 convention, she convened an Atlanta chapter and inducted over

a hundred local Atlantans into her organization. She urged them to

run for office. "If we do this we won't have to go to the table,"

she told the women. "They will seek us out."

In her address

to this gathering, C. Delores Tucker, former Secretary of State of

Pennsylvania and then chair of the DNC Black Caucus, was still

talking about how "our white sisters disappeared" in 1984.

However, she concluded "we aren't second class citizens anymore."

![]() This message of finally being accepted was common to the women's caucus

and the Jackson delegates, even though they never met together. It

was usually coupled with exhortations to unity. According to Vicki

Alexander, long before the convention, while the press was playing

up conflicts between Dukakis and Jackson, the latter's followers were

being counseled to accept compromise in order to beat Bush. However,

unlike women, the sense of acceptance for Blacks was tied to Jackson.

This is the first convention in several in which there were no daily

black caucus meetings as there were women's caucus meetings. One small

black caucus meeting was held the first day, but after that the Jackson

delegate meetings and a series of seminars for Jackson supporters

at Morris Brown college were the locus of black activity.

This message of finally being accepted was common to the women's caucus

and the Jackson delegates, even though they never met together. It

was usually coupled with exhortations to unity. According to Vicki

Alexander, long before the convention, while the press was playing

up conflicts between Dukakis and Jackson, the latter's followers were

being counseled to accept compromise in order to beat Bush. However,

unlike women, the sense of acceptance for Blacks was tied to Jackson.

This is the first convention in several in which there were no daily

black caucus meetings as there were women's caucus meetings. One small

black caucus meeting was held the first day, but after that the Jackson

delegate meetings and a series of seminars for Jackson supporters

at Morris Brown college were the locus of black activity.

![]() The one time black and white women were both present in large numbers

was Monday afternoon at a reception Voters for Choice gave for California

Assemblywoman Maxine Waters. Alexander described it as an "incredible

coming together of black, white and Hispanic women." At this

event both feminist and black leaders, including Gloria Steinem, Correta

Scott King and California Assembly Speaker Willie Brown talked about

the need for unity. The Platform speaks to the needs of all women

they said. Maxine Waters pointed out that while women may fight, in

the end they work together.

The one time black and white women were both present in large numbers

was Monday afternoon at a reception Voters for Choice gave for California

Assemblywoman Maxine Waters. Alexander described it as an "incredible

coming together of black, white and Hispanic women." At this

event both feminist and black leaders, including Gloria Steinem, Correta

Scott King and California Assembly Speaker Willie Brown talked about

the need for unity. The Platform speaks to the needs of all women

they said. Maxine Waters pointed out that while women may fight, in

the end they work together.

![]() One of those occasions was at the Democratic Party's Rules Committee

meeting on June 25 in Washington. From the NOW convention in Buffalo,

Molly Yard called for a reduction of the superdelegates while the

Jackson campaign won the vote to eliminate most of the DNC members

as automatic delegates to the next Democratic convention. This will

remove approximately 250 superdelegates -- public and party officials

not selected through primaries and caucuses -- from the current 646.

Many believe that without the large number of superdelegates Dukakis

would have had a harder time sewing up the nomination so early.

One of those occasions was at the Democratic Party's Rules Committee

meeting on June 25 in Washington. From the NOW convention in Buffalo,

Molly Yard called for a reduction of the superdelegates while the

Jackson campaign won the vote to eliminate most of the DNC members

as automatic delegates to the next Democratic convention. This will

remove approximately 250 superdelegates -- public and party officials

not selected through primaries and caucuses -- from the current 646.

Many believe that without the large number of superdelegates Dukakis

would have had a harder time sewing up the nomination so early.

![]() However, since the Democratic Party Charter requires that elected

DNC members be equally divided by sex, and there is no such requirement

for the other superdelegates, this change in the rules will make it

harder to achieve 50-50 representation for women at the 1992 convention.

Equal division has been required since 1980, but the presence of superdelegates

still tips the balance in favor of males. The 1984 convention had

50 more men than women delegates, and in 1988 there were over a hundred

more men because public officials such as Members of Congress and

Democratic governors are overwhelmingly male. Since they are also

overwhelmingly white, women were 45 % of all white delegates, but

55 % of minority delegates. Thirty-three percent of the delegates

to the 1988 convention were of black, Hispanic, Asian Pacific or Native

American heritage.

However, since the Democratic Party Charter requires that elected

DNC members be equally divided by sex, and there is no such requirement

for the other superdelegates, this change in the rules will make it

harder to achieve 50-50 representation for women at the 1992 convention.

Equal division has been required since 1980, but the presence of superdelegates

still tips the balance in favor of males. The 1984 convention had

50 more men than women delegates, and in 1988 there were over a hundred

more men because public officials such as Members of Congress and

Democratic governors are overwhelmingly male. Since they are also

overwhelmingly white, women were 45 % of all white delegates, but

55 % of minority delegates. Thirty-three percent of the delegates

to the 1988 convention were of black, Hispanic, Asian Pacific or Native

American heritage.

![]() Although women comprise between 55 and 60 percent of Democratic voters,

there was no interest in demanding that this be reflected at future

conventions. Instead, there was a consensus among feminist and other

women's organizations that the next step is more women candidates.

The third day of the women's caucus was devoted to introducing new

candidates to women activists. One of the most popular symbols at

the women's caucus was a sticker reading "5 %" passed out

by the Fund for the Feminist Majority. The number referred to the

gross underrepresentation of women in Congress, and attracted the

same kind of attention that "59 %" (women's earnings compared

to men's) did several years ago.

Although women comprise between 55 and 60 percent of Democratic voters,

there was no interest in demanding that this be reflected at future

conventions. Instead, there was a consensus among feminist and other

women's organizations that the next step is more women candidates.

The third day of the women's caucus was devoted to introducing new

candidates to women activists. One of the most popular symbols at

the women's caucus was a sticker reading "5 %" passed out

by the Fund for the Feminist Majority. The number referred to the

gross underrepresentation of women in Congress, and attracted the

same kind of attention that "59 %" (women's earnings compared

to men's) did several years ago.

![]() Women are only 2 % of U.S. Senators, 4.7 % of Members of congress,

11 % of State Senators, and 17 % of State Assembly members. The evidence

is that these low numbers are not due to rejection by the voters,

but the difficulties of mounting credible candidacies and getting

party support. Several studies have shown that when key factors such

as party label, incumbency, and money are equal, women candidates

do as well as men.

Women are only 2 % of U.S. Senators, 4.7 % of Members of congress,

11 % of State Senators, and 17 % of State Assembly members. The evidence

is that these low numbers are not due to rejection by the voters,

but the difficulties of mounting credible candidacies and getting

party support. Several studies have shown that when key factors such

as party label, incumbency, and money are equal, women candidates

do as well as men.

![]() Ellie Smeal, founder of the Fund for a Feminist Majority, said elected

women are equally divided between the Republican and Democratic Parties,

and the that "the Republican Party has done more affirmative

action in electing women candidates." However, she added, the

candidates of both parties are getting better, and women have more

power in Dukakis' campaign than in Mondale's, even though feminists

and feminist organizations are getting less attention. As an example

of the latter, she pointed out that neither of the candidates spoke

to the women's caucus whereas both Mondale and Jackson had done so

in 1984. Instead, Smeal said, "we're back to getting the wife

sent."

Ellie Smeal, founder of the Fund for a Feminist Majority, said elected

women are equally divided between the Republican and Democratic Parties,

and the that "the Republican Party has done more affirmative

action in electing women candidates." However, she added, the

candidates of both parties are getting better, and women have more

power in Dukakis' campaign than in Mondale's, even though feminists

and feminist organizations are getting less attention. As an example

of the latter, she pointed out that neither of the candidates spoke

to the women's caucus whereas both Mondale and Jackson had done so

in 1984. Instead, Smeal said, "we're back to getting the wife

sent."

![]() This was a reference to Kitty Dukakis, who addressed the women's caucus

on the last day. Despite her spousal status, her talk was enthusiastically

received, unlike Bentsen's, who spoke the day before. The day after

the convention was over both Dukakis and Jackson spoke to a meeting

of black and other Jackson delegates. Neither appeared before the

women's caucus.

This was a reference to Kitty Dukakis, who addressed the women's caucus

on the last day. Despite her spousal status, her talk was enthusiastically

received, unlike Bentsen's, who spoke the day before. The day after

the convention was over both Dukakis and Jackson spoke to a meeting

of black and other Jackson delegates. Neither appeared before the

women's caucus.

Kitty Dukakis

Molly Yard

![]() However, Dukakis did meet with over a dozen elected women at the request

of former New York Congresswoman Bella Abzug and Maryland Senator

Barbara Mikulski on the third day of the convention. The women told

him that it was important to focus on "gender gap issues"

such as the economic well being of low income women and war and peace.

Kate Michelman of NARAL and Mary Futrel of the National Education

Association were the only organization representatives present.

However, Dukakis did meet with over a dozen elected women at the request

of former New York Congresswoman Bella Abzug and Maryland Senator

Barbara Mikulski on the third day of the convention. The women told

him that it was important to focus on "gender gap issues"

such as the economic well being of low income women and war and peace.

Kate Michelman of NARAL and Mary Futrel of the National Education

Association were the only organization representatives present.

![]() There were obvious lines of tension between NOW and the mainstream

of the party, which the other women's organizations appeared not to

share. Molly Yard said she had regular communication with the Jackson

campaign, but little with the Dukakis people. Both she and Smeal attributed

this to the tendency of Party regulars to blame NOW for Mondale's

defeat in 1984. NOW was the primary mover behind Geraldine Ferraro's

selection as Mondale's running mate, and was a target of Republican

propaganda that Mondale was pandering to the special interests in

the Democratic Party. As part of its counterattack, the Reagan campaign

identified select groups of women voters with specific issue interests

and aimed commercials at them.

There were obvious lines of tension between NOW and the mainstream

of the party, which the other women's organizations appeared not to

share. Molly Yard said she had regular communication with the Jackson

campaign, but little with the Dukakis people. Both she and Smeal attributed

this to the tendency of Party regulars to blame NOW for Mondale's

defeat in 1984. NOW was the primary mover behind Geraldine Ferraro's

selection as Mondale's running mate, and was a target of Republican

propaganda that Mondale was pandering to the special interests in

the Democratic Party. As part of its counterattack, the Reagan campaign

identified select groups of women voters with specific issue interests

and aimed commercials at them.

![]() The 1984 election results showed the same gender gap that had first

appeared in 1980. Women were still 8 % more likely to vote Democratic

than men. But because the gap did not increase the press coverage

gave the impression that it had disappeared. The strategy of appealing

to women was pronounced a failure despite the fact that the exit polls

definitively showed that Ferraro's presence on the ticket did not

hurt Mondale, and probably helped him slightly. However, as in 1972,

another year in which victory for the Democratic Party was a long

shot, party leaders sought a scapegoat. That year they attacked the

changes in delegate selection rules that had resulted in McGovern's

nomination; in 1984 it was the presence of a woman on the ticket and

the role of NOW in achieving this that was the object of insider anger.

The 1984 election results showed the same gender gap that had first

appeared in 1980. Women were still 8 % more likely to vote Democratic

than men. But because the gap did not increase the press coverage

gave the impression that it had disappeared. The strategy of appealing

to women was pronounced a failure despite the fact that the exit polls

definitively showed that Ferraro's presence on the ticket did not

hurt Mondale, and probably helped him slightly. However, as in 1972,

another year in which victory for the Democratic Party was a long

shot, party leaders sought a scapegoat. That year they attacked the

changes in delegate selection rules that had resulted in McGovern's

nomination; in 1984 it was the presence of a woman on the ticket and

the role of NOW in achieving this that was the object of insider anger.

Neither NOW nor any other feminist organization endorsed any of the

Presidential aspirants in 1988. Yard said that the only candidate

which inspired NOW's membership was Colorado Rep. Pat Schroeder, who

tested the waters in the summer of 1987 after an enthusiastic reception

at the NOW convention in July of that year. Although $350,000 was

pledged to her campaign at that convention, and a test mailing showed

even stronger support, Schroeder decided that her time had not come

in 1988, and withdrew without ever officially declaring her candidacy.

Neither NOW nor any other feminist organization endorsed any of the

Presidential aspirants in 1988. Yard said that the only candidate

which inspired NOW's membership was Colorado Rep. Pat Schroeder, who

tested the waters in the summer of 1987 after an enthusiastic reception

at the NOW convention in July of that year. Although $350,000 was

pledged to her campaign at that convention, and a test mailing showed

even stronger support, Schroeder decided that her time had not come

in 1988, and withdrew without ever officially declaring her candidacy.

![]() The only feminist organization to endorse was NARAL, which played a much bigger

role at this convention than it has done in the past. To "insure

that abortion was a salient issue" it sent a packet to all delegates,

including a tape recording and literature. According to Michelman,

phone calls identified 1,500 pro-choice delegates. Although she knew

abortion wouldn't be an issue at the convention, she hopes it will

become one during the campaign.

The only feminist organization to endorse was NARAL, which played a much bigger

role at this convention than it has done in the past. To "insure

that abortion was a salient issue" it sent a packet to all delegates,

including a tape recording and literature. According to Michelman,

phone calls identified 1,500 pro-choice delegates. Although she knew

abortion wouldn't be an issue at the convention, she hopes it will

become one during the campaign.

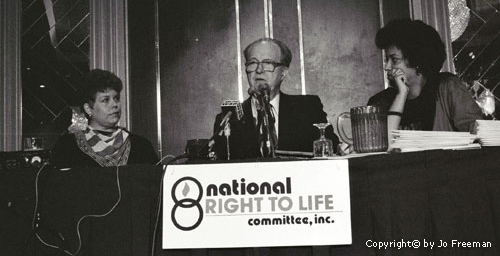

![]() Pro-life supporters share her sentiments, though their presence in

the Democratic Party is very slim. John C. Wilke of National Right

to Life, Kay James of Black Americans for Life, and Jackie Schweitzer

of National Pro-Life Democrats flew in for a press-conference to protest

"the most pro-abortion presidential ticket in history" and

flew out the same day. Copies of NARAL leaflets lauding Lloyd Bentsen

were included in their press packet. Schweitzer admitted that pro-life

Democrats "have left the party or dropped out of active participation

because of the Democratic leadership's pro-abortion position."

She will not work for the national ticket in November.

Pro-life supporters share her sentiments, though their presence in

the Democratic Party is very slim. John C. Wilke of National Right

to Life, Kay James of Black Americans for Life, and Jackie Schweitzer

of National Pro-Life Democrats flew in for a press-conference to protest

"the most pro-abortion presidential ticket in history" and

flew out the same day. Copies of NARAL leaflets lauding Lloyd Bentsen

were included in their press packet. Schweitzer admitted that pro-life

Democrats "have left the party or dropped out of active participation

because of the Democratic leadership's pro-abortion position."

She will not work for the national ticket in November.

![]() When asked when why pro-life didn't file a minority report on the

Platform, she said she couldn't find anyone on the Committee willing

to do so. She also said her home state of Minnesota sent 16 pro-lifers

to the 1984 Democratic Convention, but only three to this one. Jesse

Jackson came under particular attack from Kay James who accused him

of selling out to the feminists when he decided to run for President.

Until then, James said, Jackson was pro-life and called abortion "black

genocide."

When asked when why pro-life didn't file a minority report on the

Platform, she said she couldn't find anyone on the Committee willing

to do so. She also said her home state of Minnesota sent 16 pro-lifers

to the 1984 Democratic Convention, but only three to this one. Jesse

Jackson came under particular attack from Kay James who accused him

of selling out to the feminists when he decided to run for President.

Until then, James said, Jackson was pro-life and called abortion "black

genocide."

![]() These pro-life speakers claimed no relationship to "Operation

Rescue" which had tried to close an abortion clinic the day before.

Thwarted by the Atlanta police using background information provided

by the Georgia NARAL affiliate, 134 demonstrators were arrested. They

were detained for several weeks because they insisted on giving their

names as "Baby John" or "Baby Jane." The judge

would not set bail without knowing their real names.

These pro-life speakers claimed no relationship to "Operation

Rescue" which had tried to close an abortion clinic the day before.

Thwarted by the Atlanta police using background information provided

by the Georgia NARAL affiliate, 134 demonstrators were arrested. They

were detained for several weeks because they insisted on giving their

names as "Baby John" or "Baby Jane." The judge

would not set bail without knowing their real names.

![]() Although Dukakis has a strong pro-choice record he has given no indication

that it will be a campaign issue, in part because there is a perception

that the issue is more important to pro-life voters than pro-choice

voters. Surveys indicate that abortion is a salient issue for three

to ten percent of the voters in federal elections, and that pro-choice

supporters are ten percent more likely to vote Democratic than Republican.

NARAL argues that abortion could be a critical factor in November

but a recent analysis performed for the Alan Guttmacher Institute

by Patricia Donovan, maintains "abortion has had little or no

influence on the outcome of the vast majority of races."

Although Dukakis has a strong pro-choice record he has given no indication

that it will be a campaign issue, in part because there is a perception

that the issue is more important to pro-life voters than pro-choice

voters. Surveys indicate that abortion is a salient issue for three

to ten percent of the voters in federal elections, and that pro-choice

supporters are ten percent more likely to vote Democratic than Republican.

NARAL argues that abortion could be a critical factor in November

but a recent analysis performed for the Alan Guttmacher Institute

by Patricia Donovan, maintains "abortion has had little or no

influence on the outcome of the vast majority of races."

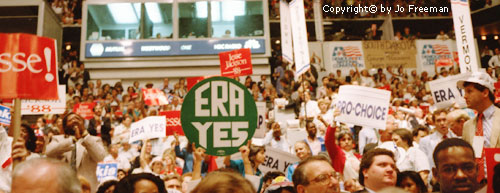

![]() Surveys conducted by the major media show that Democratic delegates

are considerably more pro-choice than Democratic voters. Nonetheless

they were unwilling to make a public issue of their pro-choice position

as reflected in the lack of signs and buttons on the second

day of the convention which NARAL had designated "choice day."

Despite NARAL's efforts to put choice stickers on delegates' lapels

and signs in their hands only a few showed in the convention arena

that night, when Jesse Jackson addressed the delegates. "ERA

YES" and other feminist signs were more popular but still lost in

the sea of red "Jesse" signs. Indeed the most visible signs

and lapel stickers of all among people attending the convention --

in and out of the arena -- were those stating "silence = death"

distributed by the Gay and Lesbian Caucus. This group still lacks

the insider status finally achieved by blacks and women, but was by

far the most visible.

Surveys conducted by the major media show that Democratic delegates

are considerably more pro-choice than Democratic voters. Nonetheless

they were unwilling to make a public issue of their pro-choice position

as reflected in the lack of signs and buttons on the second

day of the convention which NARAL had designated "choice day."

Despite NARAL's efforts to put choice stickers on delegates' lapels

and signs in their hands only a few showed in the convention arena

that night, when Jesse Jackson addressed the delegates. "ERA

YES" and other feminist signs were more popular but still lost in

the sea of red "Jesse" signs. Indeed the most visible signs

and lapel stickers of all among people attending the convention --

in and out of the arena -- were those stating "silence = death"

distributed by the Gay and Lesbian Caucus. This group still lacks

the insider status finally achieved by blacks and women, but was by

far the most visible.

Sen. Alan Cranston of CA

![]() Lack of visibility remains the greatest concern of feminist leaders,

even though its presence could threaten their insider status. The

day after the convention ended, Jesse Jackson told a mass meeting

of his followers to "keep up the street heat." Bella Abzug

privately urged her supporters to "organize inside and outside."

Blacks and women agree that the party has opened up and is finally

listening. But neither are ready to shut up.

Lack of visibility remains the greatest concern of feminist leaders,

even though its presence could threaten their insider status. The

day after the convention ended, Jesse Jackson told a mass meeting

of his followers to "keep up the street heat." Bella Abzug

privately urged her supporters to "organize inside and outside."

Blacks and women agree that the party has opened up and is finally

listening. But neither are ready to shut up.

See photos from the 1988 Democratic Convention.

Notes

1

American Association of University Women, American Nurses Association,

Emily's List, Fund for the Feminist Majority, League of Women Voters,

National Abortion Rights Action League, National Association of Social

Workers, National Organization for Women, National Women's Law Center,

National Women's Political Caucus - Democratic Task Force, Planned

Parenthood, Voters for Choice, Women's Campaign Fund, Women's Legal

Defense Fund, YMCA of the USA.

To Top

Books by Jo | What's New | About Jo | Photos | Political Buttons

Home | Search | Links | Contact Jo | Articles by Jo