SOMETHING DID HAPPEN

AT THE DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL CONVENTION

Published in Ms., October 1976, pp. 113-115.

by Jo Freeman

Related readings:

1976 Democratic Convention photos.

1976 Republican Convention analysis and photos.

Every four years I get convention fever. This is not an idiosyncratic illness; millions of Americans spend the weeks of the Democratic and/or Republican conventions glued to their television sets. But mine is an extreme case. I have to be there.

Every four years I get convention fever. This is not an idiosyncratic illness; millions of Americans spend the weeks of the Democratic and/or Republican conventions glued to their television sets. But mine is an extreme case. I have to be there.

I've attended every Democratic convention since 1960 when my mother took me to the Los Angeles Sports Arena to picket for Adlai Stevenson's third nomination. Even before the Democrats announced that New York City was the site of the 1976 convention, I knew I was going. I also knew that the opportunity for women to stick a foot inside the Democratic door at this convention would be a result not only of advance planning by feminist groups, but of dramatic struggles that had been changing the structure of the Democratic Party for years -- even decades. Shifts of power within the party, plus the growing influence of the Women's Movement, made women's demand for equal participation in the party the major debate in 1976.

I first experienced these battles in 1964 when I hitchhiked from Berkeley to Atlantic City to participate in demonstrations which urged the seating of the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in place of the all-white regular delegation. Those of us sweating in the sun, propping up protest posters on the Atlantic City boardwalk, were angered, even infuriated, when Hubert Humphrey, Vice-Presidential hopeful and longtime civil rights supporter, engineered a compromise which gave the MFDP two seats as "delegates-at-large." The Mississippi regulars, who frequently did not even support the Democratic Party's Presidential nominee, were allowed to keep all of their seats.

Two seats seemed like a betrayal to those outside. But from my brief forays into the convention hall on a limited access press pass, I knew that the delegates considered the MFDP's two seats to be an extraordinary concession. I doubt that anyone -- inside or outside -- realized then that the protest, and the compromise, portended extraordinary changes within the Democratic Party.

A key stipulation of that 1964 compromise was that at future conventions, delegations would be required to "assure that voters in the state, regardless of race, color, creed, or national origin, will have the opportunity to participate fully in Party affairs." This began a steady encroachment on the traditional right of state parties to decide the means of selection and composition of their delegations. Delegate selection became the focus of a battle between the national party and the Southern state parties that had been going on for years.

In 1968, the Democrats obligingly brought the convention to Chicago where I then lived. In great anticipation, I contracted to write a story for an obscure magazine and joined a convention research team directed by political scientist Aaron Wildavsky. It was a wild week. In between interviewing delegates at the Hilton, and protecting my camera, if not myself, from unidentified flying objects, I missed what was to become one of the most significant events of convention history.

The Democratic Party decided to create a commission to write some national rules, rules which would provide guidelines for resolving the increasing disputes over delegation selection. For the first time in American history a national party laid claim to the legitimate authority to tell state and local parties what to do.

The Commission on Party Structures and Delegate Selection was influenced by the events of 1968. As Jeanne Kirkpatrick writes in The New Presidential Elite (the Russell Sage Foundation, 1976):

The notion that many Democrats (especially antiwar, anti-Humphrey, anti-Johnson Democrats) had been frozen out of participation in the nominating process in 1968 was premise to the deliberations of the McGovern-Fraser Commission. The determination to wrest control of the party from the entrenched leadership and to "open" the party to the participation of all-- especially those formerly frozen out -- was the overriding goal of the commission.

The guidelines set forth in the commission's report, published in April, 1970, were to revolutionize the delegate-selection process. Not only were affirmative steps required to encourage proportionate representation of minorities, youth, and women as delegates, but, more significantly, the delegate-selection process was taken out of the back rooms by requiring specific rules, public selection, and public notice of all relevant meetings. In a subsequent ruling, the commission, partially influenced by the newly organized Democratic Task Force of the National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC), decided that the burden of proof for affirmative action would rest with the state party if women, youth, and minorities were under-represented in its delegation.

In preparation for the Miami convention most of the states complied with the guidelines, resulting in an increase of women delegates from 13 percent in 1968 to 40 percent in 1972. But I lived in a state whose major city -- Chicago -- did not. Mayor Richard Daley's complacency about his own powerful place in the party was not disturbed by such trivial things as national rules. His machine would elect the delegates he selected, virtually all of whom were male.

Immersed in completing my Ph.D, requirements, I did not plan to go to the 1972 convention. But Shirley Chisholm's announcement of her candidacy changed my mind. To make a long story very short, by January, 1972, I found myself running for delegate as one of only four Chisholm-committed candidates in Illinois. I came in ninth out of 24 in my district; the top eight winners were all machine Democrats. The next day I read about an impending challenge of Daley's delegation and joined in. The credentials committee awarded the seats to our challenging delegation, which fully reflected the minority, female, and youth populations of each district. Alderman Bill Singer, initiator of the challenge, took out a $10,000 personal loan to finance the plane and hotel fares of those who couldn't pay their own way (I reimbursed him for my share by selling feminist buttons at the convention), and all of us descended on Miami Beach.

The view of the world from the delegate's seat is unlike that from any other place in or out of the convention hall. One's primary identification is as a member of a state delegation. You sit together, you meet together, and receive your credentials, information, and instructions together. Although I went as a feminist and actively sought out the women's and the Chisholm caucuses, Illinois and Chicago delegation meetings took priority.

The lack of adequate communication and the haphazard notification of meetings by the other caucuses didn't help matters any. All I remember of the women's caucus is that it met, talked a lot, felt very frustrated, was betrayed on the "reproductive freedom" plank, and accomplished very little. Women were knocking on the Democrats' door in 1972, but the party didn't have to listen.

Instead, after Miami, the party listened to the backlash of the regulars who had felt excluded in 1972 and wanted back in. They blamed "quotas" at the convention for defeat in the election. The rules were changed for 1976 to emphasize good intentions rather than good results. They still required affirmative action, but if a state party submitted and followed an approved plan, it was not really held responsible for inadequate results.

"Inadequate" is precisely what women's and minority groups thought the results were. Midway through the 1976 selection process, the number of black, female, Latin, and under-30 delegates was running 15 to 35 percent less than their 1972 rate. New, complex restrictions prohibited the challenge of delegations on the basis of composition alone, so there was little that could be done for this convention. But the NWPC and the Caucus of Black Democrats didn't want it to happen again. They went to the June rules committee meetings with proposals for improvements, and an agreement to support each other's proposals. They both wanted "goals and timetables" for achieving specific results in affirmative action plans. And women especially wanted a requirement, called the 50-50 provision, that all convention delegations be equally divided between the sexes from 1980 on.

After a showdown with Carter aides, blacks and women won the first point, and narrowly lost the second. Instead, the rules committee passed a watered-down resolution asking the party to "promote equal division." But the supporters of the 50-50 provision had the necessary strength to file a minority report so that the proposal could be brought up for floor debate at the convention, and the NWPC sent an SOS to all women delegates. This fight was not scheduled until the afternoon of the last day of the convention. There would be time to negotiate, and the negotiations were to become the major point of debate in the women's caucus meetings at the convention.

National and local feminist groups began mobilizing months before the convention. Both the National Organization for Women (NOW) and the NWPC sent members to testify at the regional and national platform committee hearings. At the platform drafting meeting in June the NWPC successfully lobbied for the inclusion of 12 major points on women's rights. A compromise was reached on the controversial abortion plank, too hot to handle in 1972, simply stating that it was inadvisable to amend the Constitution to overturn the Supreme Court decision.

National and local feminist groups began mobilizing months before the convention. Both the National Organization for Women (NOW) and the NWPC sent members to testify at the regional and national platform committee hearings. At the platform drafting meeting in June the NWPC successfully lobbied for the inclusion of 12 major points on women's rights. A compromise was reached on the controversial abortion plank, too hot to handle in 1972, simply stating that it was inadvisable to amend the Constitution to overturn the Supreme Court decision.

The NWPC early created a convention coalition of its Democratic Task Force, chaired by Mildred Jeffrey of Detroit, and the Women's Caucus of the Democratic National Committee, chaired by Koryne Horbal of Minnesota and co-chaired by Patt Derian of Mississippi. Their intention was to lobby on the U.S. National Women's Agenda, a statement of general concerns and priorities of more than 100 national women's organizations, which was sent to all women delegates. NOW's intentions were to march the Saturday preceding the convention in order to publicize six priority issues, and to spend convention week lobbying. Its particular concern was the Equal Rights Amendment, since 15 of the 16 unratified states have Democratic administrations.

Betty Schlein of NOW, Mildred Jeffies of the NWPC and Koryne Horbal of the DNC Women's Caucus at the Monday morning meeting

It was becoming apparent that the feminist groups were going to perform in more than one ring of the usual three-ring circus. I not only wanted to observe it all but to measure the impact of women's groups on the delegates. I collaborated with political scientist Tommie Sue Montgomery to recruit 11 interviewers who talked to 126 delegates and alternates Wednesday and Thursday. We found that 95 percent of the women and 80 percent of the men were aware of at least some of the convention activities of women's groups, although the women were predictably better informed and less confused about their meaning. Only about half the delegates had read about NOW's march, which occurred the day before most of them arrived in New York.

In classic pressure-group fashion, NOW put an invitation to its hospitality suite -- on the strategic third floor of the headquarters hotel -- in every delegate's mailbox. Three-fourths of the women and 37 percent of the men said they received one. Several hundred showed up, but, according to suite hostess Grace Finley, public officials stayed away in droves. She said that the chairs of some delegations, such as New Jersey, even ordered their members not to come. (Nonetheless, two NOW chapters -- one in the Panama Canal Zone, one in the Midwest -- were formed during these receptions.)

While some NOW members softly lobbied, two dozen others were tracking down delegates to sign a petition demanding that the ERA be a priority issue for the party and the candidate. More than 1,500 signatures -- those of half the delegates -- were obtained and validated in three days. Though 90 percent of those asked to sign did so, not all delegates were supportive. One man tore up an almost full petition, and several other petitions were stolen. The NWPC, grown sophisticated with experience since the hectic days of 1972, staged a major fund-raiser at the Metropolitan Opera House and raised $16,000, twelve times NOW's convention budget.

This financed six rooms in the Hilton, preconvention mailings to women delegates, special phones (Pa Bell charged $2,082 for five phones for one week), and a Women's Political News Service to publicize women delegates and issues. NWPC also set up a network of contacts in each state delegation for lobbying, polling, and meeting notification, with four coordinators on the floor of the convention.

Although both NOW and the NWPC were lobbying delegates and arguing rules, it was quite obvious which organization was inside and familiar with the party structure and which was not: active party members were organizing NWPC activities; many Democratic bigwigs attended its fund-raiser; and prized convention passes for its steadiest workers were in ample supply. While the NWPC had preconvention schedules not even given to the press, I had to supply NOW with my delegate list -- available to the press but not to pressure groups -- so that it could send out its reception invitations. Convention passes for NOW's ERA petitioners were a rare luxury.

Nevertheless, NOW was looking through the crack in the door that the NWPC had opened. Asked why NOW didn't have a literature table outside the Hilton as the Right-to-Lifers did, convention coordinator Arlie Scott told one reporter, "We are inside the convention this time. We don't have time for tables." This sentiment was echoed by many NOW staffers, who, feeling the seduction of partisan politics, were thinking of running for delegate themselves next time.

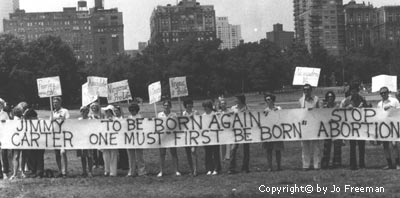

The Right-to-Lifers not only had a table outside the Hilton, they felt outside. Their march was scheduled for Sunday, and I picked that of all the competing events to attend simply because I hadn't been to one before. Standing in Central Park's Sheep Meadow watching a few thousand of the faithful gather, far less than the 100,000 they had expected, I was struck by a subtle transformation. This was the fabled "mainstream"; they looked it and they talked it. But they were confused and puzzled by the events of the last few years. They were no longer the numerical majority, and no longer felt they shared the same outlook as those in positions of power. They ran Ellen McCormack for President because none of the major candidates was actively supporting their position. While she was being nominated Wednesday night, two dozen delegations hoisted "Freedom of Choice" banners.

Gay Rights activists were experiencing the frustrations of the 1972 women's caucus. Though a Sunday march gained the attention, if not the attendance, of 60 percent of the delegates, and 600 delegates or alternates signed a declaration of support, party officials weren't very receptive to recognizing the gays as a legitimate caucus of the Democratic Party. Their platform proposals had been brought up and voted down twelve times in June, and they didn't have the 25 percent necessary for a minority report. Udall delegate Jean O'Leary, Co-Executive Director of the National Gay Task Force, had spent several exasperating days trying to get a caucus meeting room large enough to hold 100 people. Give us a list of 100 delegates who want to attend, she was told, and we'll give you the room. Other caucuses did not have this demand made of them.

Jean O'Leary

Despite pressure from women politicians and women's caucus leaders, the best the convention officials would do was give gays a room in the convention area which required passes to enter. Other caucuses had rooms in the Hilton where anyone could and did attend. For gays, not only is the door still tightly shut, but the party doesn't even bother to pretend it's listening.

The prostitutes weren't demanding that the Democrats let them in: they've been inside individual doors for years. But the New York legislature, determined to improve New York's image, didn't want them on the outside either. To keep "working girls" off the streets, it passed, effective the day before the convention, a law prohibiting "loitering for the purpose of engaging in prostitution." Majority Report, a New York City feminist newspaper, sponsored a "loiter-in" in cooperation with COYOTE, a San Francisco-based organization working to decriminalize prostitution. Every evening "square" women met several blocks from the Hilton, to be dressed and trained to act like streetwalkers and sent out in groups to "loiter." When their efforts were successful in stopping passers by, the women asked for signatures on a petition to decriminalize prostitution. No one was arrested for "loitering."

Though half the delegates and alternates surveyed heard about the "loiter-in," attending a convention is so time-consuming that activities purely on the outside are rarely seen by those on the in, especially with the tightened security of recent years. The 1972 convention hall in Miami was so well cordoned off that one day when I went looking for the demonstrations, I discovered I could neither get out nor could I find a place inside the fence from which I could see the protests.

In New York, the demonstration zone was on the opposite side of the convention hall from the delegate entrance. The press entrance was there, however, and riding up the glass-enclosed escalators permitted a very good view if the signs were big enough.

The main event for women inside the convention happened Tuesday morning. Half the 1,776 women delegates and alternates engaged in hot debate over whether to accept a compromise on the 50-50 provision for delegate selection reached between Governor Carter and a negotiating group from the women's caucus or to insist on a floor fight.

The previous Thursday, a small group of women had met in Bella Abzug's office to work out possible compromise language and discuss the other commitments they wanted from Carter in exchange for not demanding a floor fight. They mistakenly thought Carter's staff had obtained approval of the compromise before Sunday afternoon, when he met with approximately 50 women. Instead, Carter had to ask North Carolina delegate Jane Patterson, author of the minority report that supported the 50-50 provision plank, to select a smaller group to meet with him the next day to work out appropriate language.

At the Monday meeting an agreement was reached (see box) which traded off a requirement of 50-50 for major commitments to include women in the campaign and the administration. Carter had already stated that he hoped to do for women what Lyndon Johnson had done for blacks, and this agreement spelled out how.

By Tuesday morning, the NWPC had polled the state delegations and knew that the 50-50 requirement would be defeated on the convention floor. Further, the "goals and timetables" provision already won strongly implied that a proper state affirmative action plan would have to have as its goal the representation of women in proportion to their presence in the Democratic electorate -- roughly 50 percent.

Consequently, the Tuesday debate was over which was the better symbol of power: a convention floor fight which would be lost, or a successful negotiation with the Presidential candidate. With some notable exceptions, it was also a debate between the "ins" and the "outs": those who were committed to working within the Democratic Party and those who were not; those who could benefit directly by more women in the administration and those who could not; those who had been close to the negotiations and those who had not.

The delegates and alternates were seated in different sections of the room than other members of the women's caucus, and voted separately. The non-delegates, in voting and in debate, preferred a floor fight. The delegates and alternates, many of them committed to Carter and urged by his staff to attend this meeting, overwhelmingly preferred the compromise. Theirs was the vote that counted.

Despite the heated debate, or more likely because of it, most women left the convention relatively satisfied. That unifying euphoria, which the Democrats had worked so hard to attain, appeared pervasive. NOW and the NWPC gained a new respect for each other and a new sense of their complementary roles. National NOW President Karen DeCrow, who had spoken eloquently in favor of a floor fight, pointedly said she would "not characterize the compromise as a sellout." NWPC New York State Coordinator Jane Small Sanford said that on Sunday she was angry at the idea of compromise, but by Tuesday thought it was the way to go. Our study asked delegates and alternates what they thought about the 50-50 provision and the compromise. Half the minority women and 75 percent of the white women supported the compromise, while the rest would have preferred a floor fight. Ninety percent of the minority men and half of the white men favored compromise, while 35 percent of the white men didn't understand what it was all about.

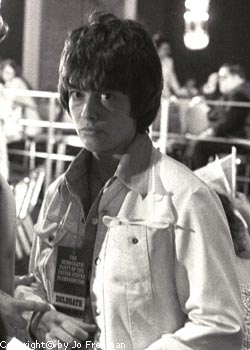

Karen DeCrow

If I had wanted to write a scenario with hasty meetings, last-minute negotiations, dramatic tension, incisive debate, major confrontations, and a modicum of suspense, in which everyone maximized their outcome, I couldn't have done a better job. Women's rights was openly debated for three hours. Those who wanted the compromise got it, and knew they got it in part because the opponents' willingness to fight made it clear to Carter that his commitment would have to be a major one. Those who spoke against the compromise realized that their role in this scenario was that of the cutting edge, the catalyst, and that they had played it successfully. Many party women approached them afterward to thank them for what they said during the debate -- things which the party women felt they could not afford to say themselves. And the delegates voted for a motion by non-delegate Gloria Allred of California that if "promotion" did not result in equal division at the 1978 midterm convention, the women's caucus would demand a rule requiring it in 1980.

The one who gained most of all was Jimmy Carter. His willingness to negotiate with representatives selected by the women's caucus impressed them and the other women delegates. This was the first time a Presidential candidate had seriously talked with them on their own terms. The outsider to the Washington establishment had made them feel like insiders. They began to feel that he could be trusted.

The one who gained most of all was Jimmy Carter. His willingness to negotiate with representatives selected by the women's caucus impressed them and the other women delegates. This was the first time a Presidential candidate had seriously talked with them on their own terms. The outsider to the Washington establishment had made them feel like insiders. They began to feel that he could be trusted.

Yet all knew that with this trust must go caution. Carter would not, could not, meet his commitments without monitoring by concerned organizations and individuals. Some will be on the inside, and some on the outside, and many will change places. All need to be conscious of their relationship to each other.

As a general rule of thumb, those on the outside can be more radical, more purist in their perspective. For this freedom to be right, they make greater personal sacrifices and receive fewer personal gains. Their benefits, if any, are collective ones, in the gains that are made for all. Those on the inside pay fewer costs, and gain more direct benefits. But they also bear the greater responsibility. They are the ones who have been pulled, squeezed, or pushed through the crack in the door. And they are the ones who have the power and the opportunity to close it after them, or prop it open.

WILL CARTER MEET HIS COMMITTMENTS?

Summary of Women's Caucus Meetings with Governor Carter, July 11 and 12:

I. The Democratic Party

- Rules Report: Recommended Language Changes: "It is hereby resolved that consistent with the traditions of the Democratic Party that the calls to the 1978 midterm convention and future conventions shall promote equal division between delegate men and delegate women from all states and terroritories. The national party shall encourage and assist state parties to adopt provisions to achieve this goal in their delegate selection plans."

- The Women's Division, which will not be subservient to the chair of the party, will be strengthened by adequate staff and funding enabling it to promote and implement feminist objectives.

- All commissions and committees of the Democratic Party will have full representation of women.

II. Campaign and Administration

- Governor Carter committed himself to making the passage of the ERA a major part of his campaign. He also stated that he would use his office, if elected President, to secure ratification.

- Governor Carter stated that the Women's Caucus can depend on his appointment of women to Cabinet posts, throughout the judiciary system, and that women will be part of the committee that will propose names for the judicial posts. His judicial appointments will be on merit, quality, and not as political payoffs. He also stated that he would seriously consider a woman for the next opening on the U.S. Supreme Court.

- The Democratic Women's Caucus will help to set up a talent bank of women listing their areas of expertise for consideration of key posts.

- Governor Carter expressed his commitment to compensatory action, necessary for women, as well as minorities, to overcome patterns of discrimination in employment.

Books by Jo | What's New | About Jo | Photos | Political Buttons

Home | Search | Links | Contact Jo | Articles by Jo