A Tribute to Coretta Scott King by Jo Freeman

View photos of Coretta Scott King below

On August 26, 2006, the 86th anniversary of the addition to the US Constitution of the 19th Amendment, feminists in New York City came together to celebrate the life of three notable American women, two of whom had died earlier in the year. They were Betty Friedan, Bella Abzug and Coretta Scott King. This is a longer version of the tribute I gave to Coretta Scott King.

I first met Coretta Scott King in September of 1966, after I had been a fieldworker for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for over a year. I'd been run out of the state of Mississippi in mid-August. Back in Atlanta, SCLC wasn't quite sure where to send me next. After CSK's full-time assistant left her employ she needed a replacement, at least temporarily. I was offered the job.

I first met Coretta Scott King in September of 1966, after I had been a fieldworker for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for over a year. I'd been run out of the state of Mississippi in mid-August. Back in Atlanta, SCLC wasn't quite sure where to send me next. After CSK's full-time assistant left her employ she needed a replacement, at least temporarily. I was offered the job.

I didn't go to her house every day; I mostly ran errands and typed letters. But when I did see Mrs. King, she talked quite a bit. I sometimes felt that being a good listener was my primary function. She worried a lot, but she never complained. Her worries were, understandably, about the welfare of her family, whose public exposure put them at risk for many things, not the least of which was their physical well-being. But she also worried about the poor and the disfranchised of the world. In her eyes she was privileged and had a duty to look out for those who weren't.

In the few weeks I knew her my admiration grew. She had two full time jobs and was searching for a third. Her first job was as the wife of a minister and the mother of four children aged 3 to 10. Dr. King was the associate pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church (whose pastor was his father). That was the family's source of income; his salary as President of SCLC was $1 a year. Ministers' wives have always had important, albeit unpaid, work in the black church, and Mrs. King did her share of ministering to the needs of the congregation. The responsibility of raising four children was also mostly on her shoulders.

Her second full time job was as the public wife of a public figure. Many wives of public figures prefer to provide support from behind, but Mrs. King embraced a public role as well. She had trained as a professional singer with the expectation of a concert career, and put her talents to good use giving concerts to raise money for civil rights. She also made speeches and appeared at public functions when called upon.

What impressed me most about her, however, was that all this was not enough. She wanted to be, she was, her own person. I learned from our conversations that she was casting about for a niche of her own, some place where she could make her own personal contribution, and not be seen primarily as the wife of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His prominence made that difficult, but I felt that when times were less intense and her children were older, she would branch out on her own with her own causes. She had already done so in small ways, such as participating in a 1962 disarmament conference in Geneva with Women's Strike for Peace.

Dr. King's untimely death made that difficult as she assumed his mantle and became his permanent representative. But her vision, like his, had always been greater than the need for racial justice. Over time she enlarged her agenda and spoke out on issues that hadn't even been contemplated during the heyday of the civil rights movement. She understood the need for women's rights to be seen as human rights, and not only spoke at feminist events but served on NOW's National Advisory Board. She was not afraid to buck conventional wisdom even within the black community, and did so by supporting the rights of lesbians and gays to marry, a particularly controversial position within the black church.

Mrs. King was not a feminist in 1966 (neither was I) but she had great respect for women. She knew that women were the hands and feet of the black church and of the civil rights movement. Men talked about what needed to be done; women got it done. But she also knew that women needed to be more than hands and feet. "If the soul of the nation is to be saved," she once said, "women must become its soul."

One result of our conversations was that I had one of those feminist "clicks" which many of us would have as we learned to see the world through different eyes. I realized that she was the first woman I had truly admired. I had admired many men (including her husband) and even tried to model myself on some of them without knowing how unrealistic that was in our society. But before I got to know Mrs. King, I had never seen women as admirable. That gave me much food for thought about how our society limits women and diminishes their achievements when I later uncovered many more admirable women in our country's history.

Before I left for Chicago in mid-October Coretta Scott King gave me a parting gift. She invited me (and one other SCLC staffer) to spend October 8 at the Georgia State Fair with the family. I shot a roll of film of the King family at play which I left with the SCLC photographer to develop. One of these days I hope to find it in the King Center archives. Those photos will bring back some very fond memories.

Coretta Scott King Photos

Coretta Scott King prepares to give the commencement speech at Roosevelt University in Chicago in 1971.

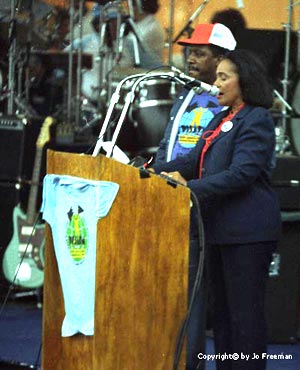

Coretta Scott King speaks at an anti-Nuke march in New York City, June 1982

Coretta Scott King finishes her seconding speech for Jimmy Carter at the 1980 Democratic Convention

Coretta Scott King is flanked by her four children as she speaks at the 1984 Democratic Convention

Page 1 2

Copyright © 2006 by Jo Freeman. Some of Jo's early civil rights activism is described in her most recent book At Berkeley in the Sixties: Education of an Activist (Indiana U. Press 2004).

Books by Jo | What's New | About Jo | Photos | Political Buttons

Home | Search | Links | Contact Jo | Articles by Jo