TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction: Feminists, Reformers and Party Women

- Myth as History

- Political Women

- Political Parties

1. Social Movements and Party Systems: Where Do Women Fit?

- Social Movements

- Party Systems

- Where Do Women Fit?

2. Cracking Open the Door: Women and Partisanship in the Nineteenth Century

- Female Reform

- Woman's Rights

- Partisanship

- Women in Politics

- Partisanship and Suffrage

3. Assaulting the Citadel: Woman Suffrage and the Political Parties

- Woman Suffrage and the Progressive Movement

- Opposition to Woman Suffrage

- Female Reform Organizations

- Feminism

- NAWSA and Nonpartisanship

4. Learning the Ropes: Emergence of the Party Woman

- The New Party Woman

- The Election of 1912

- The Election of 1916

- The Parties Respond

5. Making A Place: The Women's Divisions

- The Democrats

- The Republicans

- Success but not Survival

6. Party Organization: The Evolution of 50-50

- The Colorado Plan

- The National Committees

- The Committee Officers

- State and Local Party Committees

- The Futility of Fifty-Fifty

7. Down Different Paths: Women's Organizations and Political Parties

After 1920

- The League of Women Voters

- The National Woman's Party

- The Women's Progressive Network

- Other Feminist Organizations

- Prohibition and Repeal

- Peace and Patriotism

8. Building a Base: Women in Local Party Politics

- Bringing Women into the Parties

- Political Clubs

- Keeping Women in Their Place

- Political Machines

- Sex Solidarity and Sex Prejudice

- Illusion and Disillusion

- Female Infiltration

9. Doing Their Bit: Women in National Party Politics

- The National Conventions

- The Convention Committees

- Women's Work in Presidential Campaigns

- The Woman's Vote?

10. Having a Say: Women's Issues in the Party Platforms

11. Claiming a Share: Presidential Appointments of Women

- Expanding Women's Sphere

- Presidential Appointments

12. Conclusion

- Opportunities and Constraints

- What Women Accomplished

ENDORSEMENTS

"Jo Freeman uncovers the hidden facts of women in this century's party

politics--whether feminists, reformers, or party women--and so creates an

inside, readable, and non-partisan history of how politics really works.

Every voter, politician, women's studies, and American history course needs

this book. A ROOM AT A TIME is a landmark."

— Gloria Steinem

"This comprehensively researched and cogently writen book is the best

account we have of the invasion of American politics by women -- a process

that has extensively influenced our past and may very likely transform our

future."

— Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.

"The untold story of American women's sometimes successful efforts

to gain access and influence in the major American political parties from

the 1880s forward.

A carefully researched, crispfully written, illuminating account of progress

and frustration. I recommend it."

— Jeane Kirkpatrick

"Jo Freeman breaks new ground with her comprehensive account of the

rise of women as active participants in American politics over more than

a century. With a fine eye for human detail, she tells the story of women,

many now largely forgotten, who not only gave leadership to reform movements

but also penetrated ruling party machines. Her findings will be illuminating

to scholars and absorbing to general readers."

— A. James Reichley, Georgetown University, author of THE LIFE OF THE

PARTIES

"Draws upon the experience of many different women -- black and white,

professional politicians and amateurs, from all regions and types of parties

-- to illustrate the how the major political parties tried to ignore women,

and women's strategies for being heard."

— Shirley Chisholm, Member of Congress, 1968-1980; first woman and

first African-American to seek the Democratic Party's nomination for President,

1972.

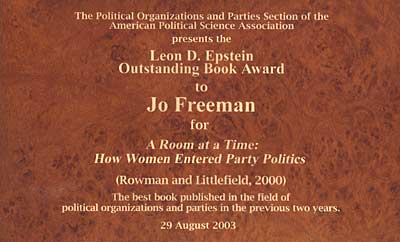

LEON EPSTEIN AWARD

This award was given by the section on Political Organizations

and Parties of the American Political Science Association at its

annual convention in late August of 2003. It honors a recently

published book that makes an outstanding contribution to research

and scholarship

on political organizations and parties The

text of the award follows:

"Jo Freeman’s A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics provides a detailed and engaging history of “party women,” a term she uses to describe those women who were involved in party organizations and helped build party support in the electorate in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Unlike more familiar female political activists, such as temperance reformers and suffragists, these women had as their primary ambition to work through the party apparatus and operate to the benefit of the parties.

One of the primary contributions of this historical study is the way it illustrates that parties, as organizations, can shape the activists that lend them service. In the case of party women, the parties gave them room to participate in ways that ensured both that the party apparatus was maintained, and that the party could compete electorally. In addition, Freeman makes a distinction between two routes through which women became influential in the parties: the individual route and the organized bloc route. The organized route was not an especially effective one for women because it required a “group consciousness” that was not encouraged by the party. Instead, individual women, who were either from political families or who had useful experience in non-political clubs, often had male sponsors who encouraged their involvement in the parties. These women were welcomed and seen as useful precisely because they were non-threatening; they were loyal to the party rather than to a cause. Yet despite the constraints placed on them by the male-dominated party organizations, the party women brought a different perspective to the political arena on a variety of issues and paved the way for the eventual acceptance of women as full participants in the political process. A Room at a Time demonstrates the numerous ways in which party women made distinctive and important contributions to the character and history of the political parties."

The Epstein

Award Committee for 2003 consisted of Marie Hojnacki, Penn State University

(Committee Chair); Alan Abramowitz, Emory University; John Bruce, University

of Mississippi; Alan Ware, Worcester College, Oxford.

REVIEWS OF A ROOM AT A TIME

VOX POP -- Newsletter of Political Organizations and Parties, An Official

section of the American Political Science Association. Vol. 19:1, Summer

2000, pp. 1-3.

by Kira Sanbonmatsu, The Ohio State University

Jo Freeman has written an important book. The result of 13 years of research, Freeman offers an insightful study of how women entered party politics. A Room at a Time is an ambitious book that spans over a hundred years and examines major and minor parties and local, state, and national levels of government. Freeman makes an invaluable contribution to political science that will be of great interest to scholars of parties, political history, and gender politics.

The book is a history of the nature and extent of women's involvement in the parties from the early 1800s to the 1960s, with an emphasis on the period since suffrage. Freeman relied primarily on newspapers as well as secondary sources in a research effort she likened to "panning for gold." She deserves tremendous credit for digging so deeply and piecing together a rich account of such an understudied and poorly documented subject. Freeman traces women's partisan involvement across time and space. The book proceeds first chronologically, then topically, with chapters on subjects such as the women's divisions, female appointments, the conventions, etc. -- each of which proceed more or less chronologically. She presents a wealth of historical data on the women's auxiliaries to the parties and the numbers, locations, and timing of women's independent clubs, with particular insights into women in New York City. She profiles key female leaders and activists and documents women's political activities -- their role in campaigns and committees, their efforts to mobilize and influence voters, their advocacy on behalf of and against machines, and their work on reform and women's rights issues. She also chronicles outcomes of attempts to influence party rules, platforms, and presidential appointments. It is a remarkable book in its breadth and depth.

Freeman identifies patterns that help us understand the opportunities and constraints facing party women over time. She situates the place of women in party politics by connecting social movements to party systems. Social movements have tended to come in clusters, including women's movements. These movements can lead to party realignments -- and when they do not, they still leave a lasting impact on politics. Women have participated in reform movements as well as women's rights movements. Most of Freeman's story takes place during what she calls the "conservative period between social movement clusters." It was during this lull in social movement activity that party women came into their own.

Freeman distinguishes between three types of political women: feminists, reformers, and party women. Party women are at the heart of her story. At times, these three groups overlapped, but at other times they were quite distinct. Reformers and feminists declined after the 1920s and divided on the issue of protective labor legislation. But party women thrived. Unlike party women before them, these women were not mobilized out of social movements first and into party politics second. This new breed of party women emerged in the early 1900s and were primarily loyal to the party.

In her work on the contemporary parties, Freeman argues that there has been an elite realignment on women's rights, with the Democratic and Republican parties essentially switching sides on feminism. In A Room at a Time, Freeman was surprised to discover what she terms the "depth of the Republican roots" in feminism. She knew that the Republican party had historically been more supportive of suffrage and the ERA than the Democratic party. Yet she finds that this legacy extends further back in time than she thought, to the 1800s. The Republican party, which had been the party of reform, was usually more sympathetic to women's rights policies and more supportive of the role of women in politics. Most active suffragists in the 1800s were Republicans. Republican women more likely to be active in politics because of their middle-class status and educational attainment, and the national party was more encouraging as well. In addition, the South, dominated by the Democratic party, has historically been weak in women's political activities.

Throughout the book, Freeman finds that Republican women out organize Democratic women. For example, Republican women's clubs persisted in between elections in the late 1800s while the Democratic women's clubs did not. As the twentieth century progressed, Republican women continued to be more likely to form clubs across the country and attract more members. It was Black women who created the first Republican women's club in New York City, and they organized dozens of Republican clubs across the country.

The metaphor used throughout the book is that of a "political house," borrowed from Democratic National Committeewoman Daisy Harriman. Women's incorporation into political institutions was slow, and they infiltrated the house one room at a time. Although women found a place for themselves and took over what Freeman terms "the basement," being the workhorses at the grassroots level, the rooms where the real decisions were made remained elusive. Women were largely the servants of the house, unable to rearrange the furniture.

The Progressive Movement helped women win suffrage and enter the political house. The minor parties were the most sympathetic to women's concerns and accepted women into their ranks first. Women won the vote despite the major parties -- not because of them. But women did gain a foothold in both major parties and gradually worked their way inside political institutions. On the eve of suffrage, both parties became interested in women's votes.

Party women were in the most demand in the 1920s -- during what Freeman dubs "the golden era" -- because women could help the parties win the loyalties of the new women voters. Women had been active in politics long before the vote and they honed their civic skills in the women's club movement. They were the experts on women's issues and organizing the women voter. The national parties and most state parties created women's divisions -- spaces for loyal party women. Party women advocated for women within the parties and educated women voters about electoral politics, serving as intermediaries between the parties and women voters. They trained women on policy issues, public speaking, and organizing.

In addition to the women's divisions, independent women's clubs were common until the 1960s, and women had more control over these clubs. In the 1920s, Democrats claimed 1,000 to 2,500 clubs, and 2,500 to 3,000 in the 1950s. The Republicans had more: the National Federation of Republican Women (NFRW) claimed 4,000 clubs and 500,000 members. Men feared the independent influence of these clubs, discouraging women from building their own machines. Women elected their own leaders, but party men could replace disloyal women with women they could control. Ultimately, men controlled the sponsorship of the women's clubs. For example, even the NFRW, which was independent from the Republican National Committee (RNC), depended on the RNC for funds. Thus the women's auxiliaries and independent clubs offered women spaces for political involvement and opportunities to train other women. But Freeman argues that they could be ghettos. Women did not occupy leadership positions over men, and they had to answer to men in the end.

Freeman argues that while Republican women were more likely to work through clubs, Democratic women were more likely to work through committees. Women in both parties frequently asked for and received "50-50" -- equal representation on the party committees -- at the local, state and national levels by law or party rule. Freeman argues that in states where women did not have 50-50, they wanted it. But equal representation did not mean equal influence. Freeman argues that "it was precisely because real influence arose from informal rather than formal relationships that women were so readily admitted onto the formal political committees." Over time, women became disenchanted with 50-50 when they realized that it did not come with influence.

Regardless of the rules, the major decisions were made by men. Adding women to the party structure did not mean a loss of power for men, who remained at the top of the hierarchy. Party men wanted loyal women committed to service -- not women interested in leadership, patronage, policy, decisionmaking, or reform. Women were lectured constantly about party loyalty, and disloyal party women were frequently replaced with loyal ones. Party men disparaged the idea that women had common interests as women or needed to organize politically as a group, denigrated the possibility of a women's voting bloc, and discouraged gender solidarity.

Power rested in the informal male networks, from which women were excluded. Women were usually ignored, unappreciated and stereotyped. Their work frequently went unrewarded, and their activities and funds could be eliminated altogether if the men so chose. Women met with considerable resistance within the parties, often frustrated by the limits men placed on their activities and power.

Despite these tremendous obstacles to their influence, Freeman argues that party women advanced the role of women within the parties and spoke for women voters. They served the party and helped win elections; they were the workhorses. They pioneered new election techniques and helped move voting from the saloons to churches and schools. They had some success in garnering female appointments and particular platform pledges. These female appointees became the "woodwork feminists" identified in Freeman's The Politics of Women's Liberation. Party women were poised to take advantage of new political opportunities when the women's movement emerged. Thus party women won not only incremental changes, but they had a long term and significant impact on women's role in politics as well. Party women paved the way for other women.

This is a carefully researched and extremely comprehensive book; it is also a compelling read. We await Freeman's next book where A Room at a Time leaves off.

PUBLISHER'S WEEKLY, Jan. 24, 2000, Vol. 247:4, p. 302.

You've come a long way baby -- or so say the cigarette ads. In reality, the journey from 1920, when women won the vote, to Hillary Rodham Clinton's overt influence on her husband's presidency in the 1990s, and from conservative reform movements like the Women Christian Temperance Union of the early 1900s to today's Concerned Women for America, is far longer and more twisted than popular history accounts for. Dispelling such commonly held myths as that women engaged in more political activism before suffrage and that there is a secure "bloc" of women voters, Freeman (The Politics of Women's Liberation) focuses on how women's political groups enabled them to move into mainstream party politics by many routes, While the WCTU and YWCA promoted "social purity" ideals, providing the opportunity for some women to gain the political know-how to engage in the electoral side of the game, hard-line political and social reformers like Florence Kelley and Molly Dewson, working closely with Eleanor Roosevelt, brought average women into the Democratic party and into the New Deal and national politics. Freeman deftly weaves together the many intricate political, moral and social complications in her story -- such as that the highly influential General Federation of Women's Clubs essentially banned the participation of African-American women -- to fashion an insightful, fascinating portrait of the ongoing fight for women to partake fully in U.S. political life. (Feb.)

CultureWatch by Emily Mitchell

Think of American politics as a big and somewhat unruly household, much in need of women. Little by little, they politely knock at the door, finally allowed in to do a little servant work of tidying up after the boys and getting rid of all those liquor bottles and spittoons. Gradually they move in a few things of their own and start to re-decorate. That's a useful metaphor for the efforts by women over much of the 20th century to be equal partners in America's political house, and in her new book Jo Freeman, a veteran editor and writer on women and politics, uses it with intelligence and grace.

There could not be a better time than this presidential election year for Freeman's study on women's entrance into party politics. During the quadrennial pursuit of the Oval Office, Democrats and Republicans play fix-it with their identities, making subtle changes in an odd kind of strategic and ideological mix-'n'-match. The media thrusts the two parties before its flawed lens, peering at the tiny surface fissures and ominous cracks that could be signs of future tectonic shifts.

Republicans and Democrats weren't always what they seem to be nowadays. John McCain doesn't seem like so much of a maverick when it is pointed out, as Freeman does, that the G.O.P. began as the party of reform and progress. As for the Democratic Party, she writes, it "was composed of marginal peoples striving to become part of American society, not to change it.'' Within the parties, Republican women were better organized, and it wasn't so much that more women tended to vote Republican but that more Republican women tended to vote. It is this party alignment, with women toiling in local and national politics, running for office and accepting appointments, that Freeman examines. She ends her book just before the Big Switcheroo began in the '60s, when the Democratic Party embraced feminist activists and the Republicans hugged the anti-fem brigade.

The party woman was a different breed from the suffragist. Her loyalty was not to a cause but to the organization. She was good for the party,domesticating it and bringing it out of the saloon and barber shop, but how good was the party for the woman? They volunteered during campaign time and were tireless in canvassing for votes, organizing rallies or passed out literature. Asked to help get men elected, they were then seldom rewarded for their efforts. As a Denver woman early in the century noted, "Women do the work and the men get the money and position nine times out of ten.'' But if the male candidate was preening in the spotlight, there was something else going on quietly behind the scenes in national committees in the women's divisions established by both parties. Whatever one may think of this gender separation, Freeman gives credit where it is due, stressing the divisions' effectiveness in educating and training women to be successful in politics.

The book traces the rise of women's influence in the voting booth and on party platforms and also looks at how the female political role grew more and more narrow over time. The emphasis for women delegates to conventions throughout the '20s and '30s had been on issues involving children and welfare.When the 1960s rolled around, women were more likely to be on show as Smiling Wife. Eleanor Roosevelt was the first to consider herself part of a political team with her husband, and her successors, notably excluding Hillary Clinton, took on Mrs. R's outward role of political partner but with little or no real influence on policy. Freeman sums it up succinctly:"The message being conveyed to party women was that who you married was more important than what you did.'' After all their loyalty, what share did women have in their government?

Eleanor Roosevelt was forceful in getting appointments for women, as was Molly Dewson, the head of the Democratic National Committee's women's division. Even with backing from the inside, some barriers remained nearly insurmountable. Freeman recounts the difficulties faced time and again by accomplished and dedicated women. One example: Judge Florence Allen, a possible Supreme Court candidate during the Truman Administration, was vetoed by Chief Justice Fred Vinson, who seemed to feel the feminine presence might detract from the way the guys managed the judicial process. A woman, he maintained, might make it hard for the Justices to settle back, take off their robes and perhaps their shoes and with shirt collars unbuttoned, discuss their problems and come to decisions. Despite obstacles, female appointments steadily progressed. The only decline, Freeman notes,was, surprisingly, under John Kennedy, and so by the time women's rights was part of the national debate,"government feminists came out of the woodwork and acted as social change agents from the inside.'' In summing up women's gifts to party politics,Freeman gets it right. Their presence helped civilize what had been a fairly unseemly process. Their appearance as poll watchers, for example, dampened the roistering atmosphere of election day. With persistence, women entering party politics made sure to push more and more doors open for the women who would be following them. If what they did has largely been forgotten, it's because their historic deeds had not adequately been acknowledged. Now they have.

* Emily Mitchell is a Senior Reporter at Time Magazine and has also written for Opera News. She was born in the Kentucky mountains and went to college in Boston. The mother of a grown son and daughter, she lives in New York City with Fred, a dog. She can be reached by email at efmitch@yahoo.comTHE

INDIANAPOLIS STAR, May 6, 2000, p. A17.

by Richard R. Roberts

It may be difficult in this age of liberated women to realize how an inferior political and legal status hobbled the lives of American women back in the days when it was declared that "all men are created equal," and what intense struggles it took to win the full citizenship and power they have today.

Jo Freeman traces their rise brilliantly in an insight-filled, ground-breaking book, A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics .

Strong, intelligent women have won influential roles in life since the dawn of time. Yet after the Revolutionary War, women's legal and political condition was not much better than that of cattle.

Even the most dynamic of women could not scale the walls to the domain of guaranteed power. But they never quit trying. This well-researched, lively account tells of their frustration and success.

Freeman notes their advances first during the social reform, anti-slavery and temperance movements of the 1830s and 1840s, next the Populist-Progressive movement of the 1880s and 1890s. These advances ultimately flowed into the New Deal and were aimed at curbing the power of big corporations and party bosses and giving power to the people. In the 1960s, women fought for greater social and economic equality, preservation and redistribution of resources and opposition to war.

The most notable victory came in 1920 with ratification of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, a giant step toward real equality.

There had been influential female reformers such as the anti-slavery Grimke sisters in the 1830s and the indefatigable suffragists such as Carrie Chapman Catt, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley and an army of others, all genuine heroines in their vigor and bravery.

Women's assault on male-dominated politics got off to a slow start once they won the power of the ballot, but soon gathered momentum.

One benefit, depending on viewpoint, was women's vigorous assault on dirty politics, boozy, low-life, corrupt politicians and vile customs that gave the whole political process a moral stench. Slowly, women forced most of the caveman types to clean up their act, and the whole country was better for it.

At first, women were nudged into minor roles. But by the 1930s, many were at home in politics and mastering the great game, running for office, winning and getting famous. Clare Booth Luce, Margaret Chase Smith, Frances Perkins, Eleanor Roosevelt, Perle Mesta, Emma Guffey Miller, and eventually Shirley Chisholm, Christine Todd Whitman and a growing throng of others, achieved great influence, authority and fame. It appeared to be only a matter of time until a woman would be elected to the highest office in the land.

As the title indicates, Freeman's book tells how women's entrance into local, state and national politics was accomplished slowly, thoughtfully, carefully, with a steely determination that even a hard-bitten male chauvinist would have to admire. It is a story of heroism, of champion gamesmanship, strong character, iron will, superb shrewdness and understanding.

What they accomplished:

First, they civilized politics, which under male dominion was a combative, rowdy, crooked, vulgar brawl. Polling places were moved from saloons and stables into churches and schools. Smoking and spitting were banned. Women became election judges and poll watchers.

Second, they accelerated the shift in campaign techniques from emotional appeals to an emphasis on facts, insisting that candidates offer voters more than patronage and pablum.

Finally, they laid the foundation for increasing women's role through education, legitimation and infiltration. The results eventually changed the entire nature of American politics. They did it "slowly and persistently, with great effort, against much resistance, a room at a time," in the author's words.

Freeman has done a masterful job. She holds a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Chicago and a J.D. from New York University School of Law. Her book, The Politics of Women's Liberation , won a prize in 1975 from the American Political Science Association for being the best scholarly work on women in politics.

Scholars, women thinking of entering politics, and all others interested in further research will benefit from her 68 pages of excellent notes and 27 pages of references.

Politics buffs are certain to find this book rich in insights into one of the most significant, continuously evolving realities of American life.

Roberts is retired chief editorial writer for The Star.

WOMEN'S

REVIEW OF BOOKS, July 2000, Vol. 27:10/11, p. 13.

by Ruth Rosen

HIGHLIGHT:

Focus on ordinary women who made advances in the American political system

which lead to much of the political freedoms available to women today

BODY:

I still remember exactly when I heard that the Democratic National Convention had nominated Geraldine Ferraro for the Vice Presidency. I was in a remote village in a little-known island in the East Aegean, the kind of place that tourists don't visit and where you simply find a room in someone's home. As I sat under a hot afternoon sun, the owner of the only bar in the village suddenly appeared and excitedly told me the news: a woman had just been nominated for Vice President of the United States.

To my complete surprise, tears suddenly spilled down my face. Even if you have as little faith in party and electoral politics as I do, that nomination seemed like a miracle to this veteran second-wave feminist. Of course I knew how much she owed her nomination to the political struggles waged by the modern women's movement. What I didn't know was the history of women in party politics who had helped pave the way.

This is the subject of Jo Freeman's splendid new book, A Room at a Time. A second-wave pioneer activist as well as a political scientist, Freeman focuses neither on political radicals nor feminists, but on the ordinary women who gradually carved out a space for themselves within the American political party system. These women, as she writes, "were not radical and they were not trying to change the world. They weren't even trying to change their parties. What they mostly wanted was inclusion, with equal reward for equal service."

Freeman's story begins in the mid-nineteenth century when women reformers were able to set the political agenda -- advocating temperance, demanding custody of their children, fighting to own property, insisting on having their own legal identity and organizing for abolition -- even though they had no political legitimacy or suffrage. She ends her history just as the second-wave women's movement began to transform American politics in the 1960s.

The history of women's political activities before 1920 is not entirely new. Freeman carefully builds on the work of historians who have described some of the characteristics of women's political and moral reform movements before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. She imagines political parties as a giant house, into which women slowly entered, one room at a time. "At the beginning of the nineteenth century," Freeman concludes, "there was only the bare framework of a political house and women were merely observers. By the end of the century the house was built. Women were still outside, but they had cracked open the door."

Freeman really hits her stride when she investigates American women's entry into the byzantine world of politics after 1920. Here is the story of the women who joined the Women's Divisions of both parties, established by men in order to gain the loyalty and support of female voters. These are the women who created political clubs to educate themselves about urban planning, agricultural policies, poverty, housing, family problems and the needs of youth. Here is where they learned to articulate policy, as well as to argue with force and passion. This is how they learned much-needed political skills.

At the same time, they still worked as campaign volunteers as Freeman notes, they made the coffee, but were excluded from creating or influencing the political platforms of each party. Although they didn't run for office, these women fought for seats on party committees, only to discover that men made the real decisions elsewhere -- in informal networks and gatherings.

Both parties utilized such volunteer "party women" for forty years, hoping that they would help nail down women's votes for their candidates. It was only during and after World War Two that these volunteers began to develop higher aspirations. Increasingly, party leaders looked to them to hand over "the female vote." Given that mandate, party women began to gain a greater sense of importance, even a sense of entitlement. Now they expected that they -- or other women -- should be rewarded with political patronage for all the flyers they had folded and all the envelopes they had licked.

During the 1960 presidential campaign, both the Democratic and Republican parties worried that an undecided "women's block" might influence the tight race between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Each party held "kaffe klatches" for women voters and tried to persuade women to vote for "their" candidate. When Kennedy Won by the slimmest of margins, women in the Democratic Party expected to be rewarded with female appointments to high-level positions in the new administration.

But Kennedy failed them miserably, and they were no longer shy about expressing their disgruntlement. In my own research into this period, I discovered many voices that expressed the disappointment that Freeman describes. In a Saturday Evening Post issue in 1960, for example, one indefatigable female party activist complained that women formed the "hard core" of political organizations but received little recognition for their efforts: "They work at the neighborhood level as block captains, poll watchers, checkers, election day baby sitters and chauffeurs. They staff party and campaign headquarters. They get out the vote and raise funds...In short, woman power has the same untapped creative potential as atomic energy!" And yet, she noted, they never received any recognition -- or appointments -- for their political work.

Democratic Party women bitterly complained about the discrimination they faced within party politics. In the same article, another woman activist condemned the "antediluvian male politicians" who "talk down" to the "dear little women" and "try to flatter their looks, rather than their aspirations." "I get awfully tired," the magazine quoted yet another leader of women in the Democratic Party, "of being treated as if I were the English speaking delegate from another planet...There are too many popular cliches about women. Why must we be typed as fluttery females or bespectacled baffle axes? The public image of women has reached an all time low not in fact, but in print. More of us are working, more of us hold better and more responsible positions than ever before but you'd never know it if you had to depend for information on what you read about women....Let's insist on speaking and acting as individuals who have a rightful place on the human planet."

By 1961, the well-known journalist Doris Fleeson was commenting in her New York Post column that "At this stage, it appears that for women, the New Frontiers are the old frontiers." In a letter to President Kennedy, veteran Democratic activist Emma Guffey Miller informed Kennedy that "It is a grievous disappointment to the women leaders and ardent workers that so few women have been named to worthwhile positions....As a woman of long political experience, I feel the situation has become serious and I hope whoever is responsible for it may be made to realize that the result may well be disastrous." Depressed and disillusioned, another party activist quoted in the Saturday Evening Post predicted that fifty years would pass before the country elected a woman president. Another grimly joked -- as it turned out, accurately -- "Man will walk on the moon before there is a woman chief executive."

By the early 1960s, these party women were no longer satisfied to staff local offices or organize bake sales. Although they didn't yet imagine fielding women candidates for electoral office, they did expect qualified women to be appointed to positions throughout the administration. Summing up these pre-women's movement decades, Freeman writes, "More than forty years after party men opened the door of the political house, women could dust the furniture and wash the dishes, but could not sit in the rooms where the decisions were made."

Still, they never gave up. Esther Peterson, for example, a veteran labor and party activist, pushed Kennedy to create the first Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. As a critical mass of these women gained a growing sense of gender consciousness, they began to seek greater influence within political parties. Gradually, a network of women who had gained experience in party politics began expanding their horizons. By the mid-sixties, they began to challenge the deeply ingrained belief that women belonged at home, not in politics. Eventually, they would help form the National Organization for Women, as well as the National Women's Political Caucus, which began fielding women candidates for electoral politics.

For readers unfamiliar with post-World War Two political history, A Room at a Time offers delicious surprises. Freeman finds that the Republican Party, for example, "displayed more gender consciousness and sex solidarity that did Democrats. Their magazines, their campaign literature, and their general admonitions were more likely to treat women as a group, with specific interests or a special viewpoint, deserving of special representation, than those of the Democrats." She argues that "When the Republican Party embraced antifeminism in the 1980s, it threw away its heritage." Some readers may also be surprised to learn that it was Lyndon Johnson who actually set a precedent for appointing a large number of women to high office.

A Room at a Time covers an extraordinary range of subjects, and yet, as Freeman herself notes, "this book is just an introduction, an invitation to explore the field of women's work in mainstream politics. Only after many local studies have been written will the building blocks exist to construct a solid edifice." Still, she has made an important contribution to our knowledge of how ordinary women, in the wake of gaining the vote, entered party politics and through their volunteer efforts began to learn how to participate in the political system. Through their determination and perseverance, they helped pave the way for the short-lived Presidential candidacies of Shirley Chisholm in 1972 and Elizabeth Dale in 1999, for two women senators -- Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer -- from California, for Christine Whitman's ascendancy to the Governorship of New Jersey, for Hillary Clinton's senatorial candidacy in New York, and for the hundreds of women who serve on local city councils, county boards and state legislatures throughout the country.

True, this is not the stuff of high drama, unlike the heroic history of the suffrage movement or the inspiring visions and unconventional antics of counter-cultural radical women activists. But we badly need to know this neglected story. As plodding as mainstream electoral politics may be, this is why we have women in Congress who protect our reproductive rights and our health concerns, and try to advance working women's needs for a higher minimum wage, paid maternal care and child care. Just as we needed women protesting in the streets, we also need women at every level of political office -- something that these party women eventually turned into a political reality.

Ruth Rosen is a Professor of History at the University of California at

Davis.

H-NET

BOOK REVIEW

Published by H-Pol@h-net.msu.edu

(November, 2000)

Reviewed for H-Pol by Kristie Miller krste@aol.com,

National Coalition of Independent Scholars

A Positive Slope Over Time

"Sometimes myth becomes history," Jo Freeman notes in her introduction to A Room at a Time (p. 2). Freeman challenges a number of still-common assumptions about women in politics: that suffrage marked the entrance of women into politics; that the only form of political expression women had was voting; and that, even with the vote, women were politically ineffective after 1920 until the second wave of feminism peaked in the 1970s. These myths have been challenged before, and Freeman summarizes and extends the findings that have undermined them.[1] But the strength of this new book is in the wealth of detail Freeman offers in describing the heretofore unrealized extent of women's participation in party politics.

Freeman presents an overview of the topic accessible to students or interested general readers, as well as a rich resource for the committed scholar of women in partisan politics. "Context is crucial to political history," she explains, and devotes one chapter to a discussion of social movements and party systems and another to suffrage and political parties (p. 9). Freeman describes women's strategy after suffrage, staking out their own territory within the parties, and their disillusioning discovery that equal representation on the national committees did not mean equal influence. She then details women's activities in local party politics as well as at the national level, their record in getting women's issues included in party platforms, and their success in securing presidential appointments.

Freeman's use of extensive primary sources certainly gives her the material to make important and original conceptual contributions. She defines three types of female political workers: feminists (i.e., suffragists), reformers, and party women. While there are many books about the first two types, Freeman emphasizes the third group, which has received scant attention until recently. During the period between the two major women's movements, Freeman contends, only the third group thrived.

The scope of her book includes discussions not only about women's activities but also about the differing strategies of the parties in assimilating women. Although Freeman is refreshingly candid about her own political preferences -- "I am a Democrat, as are most of the people I speak to," she admits (p. x) -- she is scrupulously fair about crediting the Republican party with having been more welcoming to women for more than fifty years. She notes that the Republican party was more hospitable to feminists between 1870 and 1920, while the Democratic party became home to most of the reformers after 1920.

Women were not trying to change the parties, Freeman argues, but only wanted to be included in them, and to receive equal rewards for equal service. Their opportunities came during periods of uncertain electoral outcomes, "when both parties look[ed] for new sources of strength and often f[ou]nd them in women, whether as voters or workers" (p. 24). She notes that women were most successful when they had sponsors; wives and widows of important men were rewarded more than the party workhorses. Still, she believes that the 1970s women's movement would not have been as successful without the groundwork laid decades earlier by party women. She draws a parallel in this regard to the suffrage work at the end of the nineteenth century that led to significant gains when the Progressive movement changed the political climate.

Women during the period between 1920 and 1970 sometimes voted as a bloc, another underappreciated phenomenon. Freeman's research turns up early "gender gaps," notably women's clear preference for Herbert Hoover in 1928, and for Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956. She shows persuasively that a "gender gap" may be due to two different components, turnout as well as preference, and explores the socio-economic basis for the former.

In addition to these larger themes, Freeman offers several other thought-provoking observations. Surprisingly, the early 1960s, not the 1950s, seems to have been the nadir of women's political effectiveness. Under John F. Kennedy, presidential appointments of women declined for the first time since 1912. The equal rights amendment, part of the Republican party platform since 1940, was dropped in 1964.

Freeman's clear and lively writing brings the stories behind these ideas to life. The book is helpfully organized by subject, rather than strictly by chronology. Freeman presents a good combination of overarching trends and themes, as well as specific state-by-state detail. To help organize the mass of detail, she uses an extended metaphor, the political house being infiltrated by women "a room at a time." However, a comparison in Freeman's conclusion would really seem to be more apt: "If one could plot women's entry into politics on a graph, one would see long periods of slow but steady increase, punctuated by a sharp rise for a few years, followed by a bit of a decline, and another slow, steady increase" (p. 227).

A Room at a Time is the result of thirteen years of research and six years of writing. Freeman cautions that those who want to write women's political history face myriad challenges. As Freeman well knows, "The study of women and politics is the study of grassroots political activity," and "women's political history is scattered and buried in many places" (p. x). Despite her detailed treatment of the subject, Freeman modestly maintains that her book is just an introduction. She calls for new local studies to furnish the "building blocks" for a "solid edifice" on women's history in politics (p. x); she also argues that another book is needed on women in party politics after 1970, as well as a book on why the Democratic party is now feminist while the Republican party is not. Many of the women who appear briefly in her pages deserve chapters or even whole biographies. In the meantime, A Room at a Time is likely to keep us happily occupied for quite awhile.

Note:

[1]. See for example, Kristi Anderson, After Suffrage: Women in Partisan and Electoral Politics Before the New Deal (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Blanche Wiesen Cook, Eleanor Roosevelt: Volume One, 1884-1933 (New York: Viking, 1992); Eleanor Roosevelt: Volume Two, The Defining Years, 1933-1938 (New York: Viking, 1999); Nancy F. Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987); Hope Chamberlin, A Minority of Members: Women in the U.S. Congress (New York: Praeger, 1973); Robert J. Dinkin, Before Equal Suffrage: Women in Partisan Politics from Colonial Times to 1920 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1995); Melanie Gustafson, Kristie Miller and Elisabeth I. Perry, eds., We Have Come to Stay: American Women and Political Parties, 1880-1960 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999); Kathryn Kish Sklar, Florence Kelly and the Nation's Work: The Rise of Women's Political Culture, 1830-1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995); Susan Ware, Beyond Suffrage: Women in the New Deal (Cambridge: Harvard, 1981), as well as biographies of individual women like Dorothy M. Brown, Mable Walker Willebrandt: A Study of Power, Loyalty and Law (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1984).

by Janet Clark, State University of West Georgia

Jo Freeman's latest book is her correction of the misconception that women first entered politics after receiving suffrage in 1920 and of the political myth that feminism failed by not organizing women into a major political force. By using analogies and detailed information, including names and places, she shows that women had already been in politics a considerable time by 1920 and that they got suffrage because of their political involvement. She describes three major types of female political activists: feminists, social reformers, and party women. Using the analogy of a braid, she shows the relative strengths of each grouping and how they wove together and unraveled at different points in the struggle for women's political power. She focuses in this book on party women to overcome their relative neglect by previous scholars. She starts with women's political activities before achieving suffrage, weaving together the actions of suffragists, reformers and party women but concentrates mostly on their work between 1920 and 1970. Using the analogy of a political house, she tells the story of how party women gradually infiltrated politics as individuals working from the bottom up, laying the foundation for the accelerated progress of the new feminist movement which begins as her story ends.

The book clearly marks a massive research effort and is thoroughly documented. Freeman journeyed through time and geographic space to gather women's political history which she found scattered and buried in many places; among women's personal papers and newspaper reports. She sees this book as an introduction and invitation to others to explore. Yet, it provides a comprehensive overview of women's political history integrated with that of American political parties. She has a mastery of how politics works in America and accurately describes the historical development and operation of six different party systems.

Throughout the book Freeman brings together the complex strands of women's political activity and integrates them with the major features of the political environment. She explains how the women's movement rises and ebbs with other important social groupings and what each strand contributed to women's lives. Her analysis combines the effects of sex, race, ethnicity and class with partisanship, never losing sight of the fact that women, like men, have different political priorities depending upon their place in society.

It was the Republican Party, among the two main ones, that first welcomed women and allowed them entrance into the foyer and basement of the political house. The social status, reform interests, and racial loyalty of politically active women made it their natural choice in the fourth party system. However, as the GOP shifted toward social conservatism, the Democrats absorbed its progressive elements into the New Deal, pulling the support of women into the party of equality. Thus, the Democrats were in a favorable position to benefit from women's increased political participation with the rise of the new Women's Movement in the 1970s.

The book provides a wealth of detailed information on women activists and social groupings over a long and particularly complex historical period. It wold be a useful supplement for courses on political parties, social movements, and women in politics. Nevertheless, to some degree, its strengths are also weaknesses. At times the reader feels overcome by Freeman's use of details to buttress her arguments. One is awash in the alphabetical soup of organizational titles, leaders' names, and shifts in geographical locations. Occasionally, the movement among the various strands of activists and levels of politics can be confusing. Yet, overall the book succeeds.

Freeman never loses sight of her main goal -- to show the impact of women on American party politics. She illustrates how they gradually forced their way into all American political institutions, and did so over the opposition of party men who welcomed their hard and effective work for the party but tried to deny them the rewards; public office and inputs on policy positions. In the end, women overcame the multiple barriers to their participation and made important contributions to American politics. Their presence "helped civilize politics" (p. 234), making it less combative and more hospitable for women and men. They "accelerated the shift in campaign techniques from emotional appeals to an emphasis on facts" (p. 235). Moreover they "prepared women for political work and enlarged their sphere of activity.... Party women did was possible to do ... slowly and persistently, with great effort, against much resistance, a room at a time" (p. 235).

by Mary Thom

While the stories of suffragists and reformers such as Jane Addams of Hull House are better known since the advent of women's studies, the history of party women has been neglected until now. in A Room at a Time, feminist Jo Freeman puts on her political-scientist-historian hat to tell us how women were active politicians in the United States long before they voted for the first time nationally in 1920. Some nineteenth-century women, for example, were highly prized political orators. Republican Anna Dickinson, at age 22, was hailed as the American Joan of Arc in 1864; journalist Ida B. Wells went stumping for GOP candidates in the 1890s; and Jane Addams seconded the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt at the Progressive Party convention in 1912.

Ironically, after winning the vote, suffragists were first courted by the major parties and then, having achieved enough leverage to make demands, squeezed out. Although valued for their organizing talents and for their votes, women were discouraged from even taking sides in a primary contest. Freeman concludes that women who remained party loyalists must have found the work its own reward, since male leaders held the reins of power so tightly. Eleanor Roosevelt said as much in 1928 when she publicly urged women to organize as women and choose their own bosses.

Freeman makes the case that through the first half of the twentieth century, women with political power usually either belonged to a powerful political family, like Eleanor Roosevelt, or proved themselves through loyalty to men. Things were changing by the 1960s, but not much. Freeman tells how Liz Carpenter, soon to be one of the founders of the National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC) helped get women jobs in Washington. Lyndon Johnson, partly to bring in new appointees who would make the administration his own after John Kennedy was assassinated, vowed to end what he called "stag government." Carpenter, who as Lady Bird's press secretary hardly held a position of great power herself, was pulled into Johnson's office and told to identify suitable women candidates for administration posts. Because Johnson insisted that agency heads report directly to him, he achieved impressive results in his effort to increase the role of women in his administration: 150 new appointees and many more promotions.

Part of a review essay by Kristi Andersen, Syracuse University, appearing in WOMEN & POLITICS, Vol. 23/4, 2001, pp. 102-104.

Jo Freeman's masterful A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics shares many of the good qualities of her earlier The Politics of Women's Liberation. Freeman has an amazing ability to gather enormous numbers of facts from varied and sometimes obscure places. Even more important, by simplifying and clarifying multifaceted phenomena she provides the reader with frameworks to make sense of complex processes. Her earlier work provided such a framework for understanding the development of the modern women's movement, from origins as diverse as presidential commissions, the civil rights movement, and catalysts such as the publication of The Feminine Mystique. Similarly, A Room at a Time develops a compelling argument about the ways that women's involvement in electoral politics developed out of moral reform and women's rights activities. Freeman proposes that female activists in the nineteenth century can be placed in three overlapping categories - they were "feminists," "reformers," or "party women." She is obviously most directly concerned with the third group, but it is useful to understand why and how women made particular choices about how to push the system, and to keep in mind the connections among the different paths. Freeman begins with background chapters that cover female reform organization and the suffrage movement. By the beginning of the twentieth century, she argues, "party women were just emerging as a distinct strand of political activist" (p. 59). By 1916, over four million women could vote in the Presidential election, and women were active in parties across the country (her discussion of this era is a nice parallel with Edwards').

Women's initial strategy to establish themselves in the party after suffrage was granted nationwide was to stake out a territory exclusively theirs: the Women's Divisions of the parties, which provided a way for the parties to mobilize women, conducted educational programs for women, as well as acting as "advocates for women within their respective national parties" (79). At the same time, and more controversially, women asked for places on the "regular" party committees. The so-called "Colorado Plan" -- for every committeeman at every level, there would be a committeewoman - became known as the policy of "fifty-fifty" and was a central goal of party women for many decades after suffrage. Women themselves were divided over the efficacy of these policies (whether instituted by state law or party rule). Women's positions were usually explicitly or implicitly subordinate to male roles within the party, and evidence suggests that "regardless of the rules, major decisions were made by men" (113).

Freeman also discusses the potential for a woman's party that was represented by the League of Women Voters and by the Woman's Party, as well as - briefly - the work of other women's organizations after suffrage. She offers a fascinating description of the little-studied women's political clubs, their conscious separation from men's clubs (which persisted into the 1960s) and their ethnic homogeneity as well as a brief survey of women in the urban party machines. In chapter 10, Freeman discusses the presence (or, more often, absence) of women's issues in the national party platforms, tracing the parties' concerns with protective labor legislation in the twenties and thirties and the emergence of an equal rights orientation in the 1940s, as well as the appearance and disappearance of the ERA on party platforms. Finally, chapter 12 examines the connection between party work and political appointments for women, concluding that "presidential appointments of women was the one area in which there was steady progress from Taft's appointment of [Julia] Lathrop in 1912" (216).

At the end, Freeman's conclusions are evenhanded. "The male response to party women was pretty much the same as their response to women's invasion of other male domains: a few women were rewarded as individuals, but the doors of opportunity were closed to women as a group" (220). However, she reminds us, these earlier activists constructed a foundation of work, experience, and contacts, and after 1970, "when the political opportunity structure opened up, women in both parties were ready to take advantage of it" (225).

Historians have "leached out" women and women's stories in constructing stories of partisan politics. These three volumes help immeasurably to bring women back into the story of party politics for the past hundred and twenty years or so. They teach us valuable lessons about the difficulty of changing power structures and about women's long and difficult struggles to do so.

Reviewed by Millie Jackson, Grand Valley State University.

Published by H-PCAACA (March, 2001)

Ruth McCormick, Molly Dewson, Harriet Upton Taylor. Most readers will probably not recognize these names. However, these women, along with many others, learned about issues and organized women so they could enter into party politics. These are only a few of the women who are the focus of Jo Freeman's volume, A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics.

Through extensive archival research Jo Freeman has drawn together the history of women's political activities in the twentieth century. While this well documented book provides the reader with a history up to the 1970s in America, it concentrates on the decades between the two world wars when women laid the foundation for work in political parties. Freeman demonstrates how women fought for their places in party politics and proved loyalty to the parties. This book is a comprehensive addition to the political history of women in the 20th century. It is an important addition to the work that has been done on 19th century women's work in politics and in social causes as well.

The focus of this study is not only on women's issues, however, it is on women working for the party. The importance of being a party woman is emphasized in this history. According to Freeman, men welcomed women so they could do the difficult work. For example. Republican men assigned women to "canvass the most intransigent Democratic districts that were loyal to Tammany Hall" (230). The women had to be interested in the good of the party, not just in issues relating to women in order to gain a place in the party structure. She traces women's entry into and advancement through the party machines and into elected office. This is the story of the women who worked at the grassroots, the county, the state and the national levels to make women's voices heard and make their voices count.

Freeman documents the work of women in both the Republican and Democratic parties. Some readers may be surprised at Freeman's findings that Republicans were more liberal than Democrats up until the late 1960s and early 1970s. More opportunities existed for Republican women to serve their party than for Democratic women. The Progressive Movement and the suffrage battles of the early twentieth century are highlighted in the discussions. Both influenced women's involvement, though the suffrage movement did not sway party politics as much as some might expect.

Freeman also discusses the interactions with traditional women's organizations which flourished in the early part of the twentieth century. Many of these organizations focused on issues that were important to women but not necessarily important to the party. Influences of groups such as the League of Women's Voters, initially viewed as dangerous and subversive, are discussed. The development of fight for the ERA is also discussed throughout the book.

The book is a remarkable history of women in general and a few influential

women in particular. Persistence and hard work were the key characteristics

that gained women a place in the rooms of political parties. Women moved

slowly and steadily into roles that were more important in party politics.

Despite setbacks along the way, they did not give up. This will be a useful

volume for political historians and scholars in women gender studies.

Party Politics

September 2001,

pp. 658-59

Reviewed by Joni Lovenduski

The observation that men and women tended to vote the same way long ago has led political scientists to regard men as the political norm. This observed similarity was somehow extended to political activism and the normal party activist was assumed to be male in the same way that the normal politician was assumed to be male. Neither observation nor assumption turned out to be true; recent feminist scholarship has shown both the observation and its extension to be an oversimplification of a complex, gendered and changing reality. In her important new study of women and American party politics, Freeman shows that women did not normally vote at the same rate as men until the 1980s, but that they sometimes outvoted men. Women were less likely to commit themselves to a particular party when they registered to vote. Since the 1950s, however, more and more men have also been registering "independent".

American women were involved in party politics before the vote was won. By the beginning of the twentieth century there were three main types of woman political activist -- feminists, reformers and party women. Often their work was co-operative, their activities intertwined. However, party women were a distinctive strand of what Freeman calls "a somewhat frazzled braid" and have a history of their own. The pattern outlined is one of long periods of slow increase in the numbers and status of party women, followed by a brief but sharp rise, then a brief decline and a resumption of the long slow increase. Two main strategies were pursued: getting women on party committees and creating special political clubs for women. That history is marked by generational shifts, major disputes and significant achievement. The popular, trivializing image of worker bees concealed a reality in which women party activists ensured the political training and education of women in a long (and continuing) march toward equality of political representation.

The progress of women in American political parties finally came when feminists outside were in the ascendant in the form of the vibrant Women's Liberation Movement of the 1970s. Ironically, when the Republican Party embraced anti-feminism in the 1980s, it threw away its heritage. Freeman describes how, until 1970, the Republican Party was more supportive than the Democratic Party of women party workers, more successful in organizing and educating women, and more likely to support the feminist position on issues when there was an issue. It was also the major beneficiary of women's votes until then.

What was accomplished? How if at all did party women make a difference? Freeman suggests three important achievements. First, politics was civilized, with smoking and spitting removed from party meetings, polling places removed from saloon, barber shop and livery stable to churches and schools, and behaviour altered accordingly. Thus, the entry of women signalled a vast change in party political culture. Second, party women accelerated a shift from emotional campaign techniques to an emphasis on facts. Women came into politics via discussion groups in which they expected candidates to present them with argument supporting a vote for them. Finally, party women prepared the ground for other women and thereby enlarged the sphere of political activity of women.

The feminization of politics depends on the nature of the parties, the opportunity structure of the times and the surrounding women's movement, especially how interested the movement is in political representation. For a few years after women won suffrage in each state, efforts were made to seek our women to run for office, but these always stopped after a short period of time. In practice, the representation of women is inevitably constrained by the nature of party politics at the time it is sought. In the USA, the lack of party competition in most places during and after the campaigns for women's suffrage meant that parties had no incentive to alter their candidate slate patterns. Women's claim for representation was undermined by the fact that by the time they got the vote, extensive areas of one-party dominance made it unnecessary for parties to win women's votes.

A Room at a Time is a major work of political history. The book redresses a significant imbalance. Until recently the study of American political parties has been a gender-blind affair in which neither the activities of women nor the impact of gender were thought to be of interest. Freeman regards her book as an invitation to explore the field of women's work in mainstream politics. It is clearly a labour of love, the product of 13 years of research and 6 years of writing. Framed in the slightly awkward metaphor of a many-roomed house, progress in the parties was made one 'room at a time.' Freeman exposes and examines myths about political women as their activities are traced through successive stages of the party system.

This book is a treasure trove, carefully crafted from local records and contemporary sources. The notes are as interesting as the main text. The findings are strong and challenging. The achievement is an excellent foundation and an irresistible invitation to further research. Let's hope it is taken up.

Joni Lovenduski

Birkbeck College

Books by Jo | What's New | About Jo | Photos | Political Buttons

Home | Search | Links | Contact Jo | Articles by Jo