Honors and Awards

- Best Scholarly Work on Women in Politics 1975

- Brookings Fellow 1978-79

- Congressional Fellows Program 1978-79

- Root-Tilden Scholar 1979-82

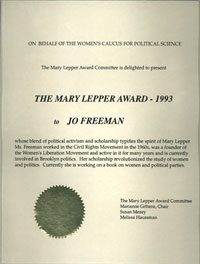

- Mary Lepper Award 1993

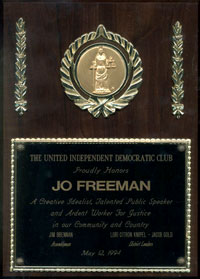

- United Independent Democrats 1993

- Susan B. Anthony Award 2000

- Political Guru award 2001-2002

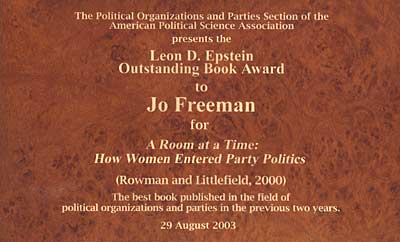

- Leon Epstein Award for Book of Distinction 2003

- Keynote Graduation speaker 2004

- Alumnus of the Week September 20 - 27, 2004

American Political Science Association prize for the Best Scholarly Work on Women in Politics (for Politics of Women's Liberation) 1975.

Awarded at the annual meeting held in September 1975

"The decision of the American Political Science Association to offer a prize for the best scholarly work on women in politics to mark International Women's Year brought its committee a dozen varied and interesting books and manuscripts from which to make a selection. In judging them, the committee used four criteria: The originality of the research, in terms of topic and methodology; the quality of its level of analysis; the effectiveness of its communication; and the recognition by the author of the limitations of the data used, and of possible biases in its use.

On this basis, the entry selected to receive the prize for the best scholarly work on women in politics was Jo Freeman's The Politics of Women's Liberation: A Case Study of an Emerging Social Movement and Its Relation to the Policy Process, published by David McKay Co. Ms. Freeman analyzes the evolution and character of the women's movement of the 1960s and 1970s with clarity and verve, effectively exploring the interaction between group action and public policy. In addition to using a wealth of background material, she has extensively interviewed a large number of individuals who were directly involved in women's movements, as well as people in government, the press and elsewhere who had an effect upon these movements. While she demonstrated a healthy awareness of the limitations of her data, she provided new insights and a useful framework within which to continue to analyze the relation between women's movements and public policy.

Two works which were both concerned with women in state legislatures were selected for honorable mention: Jeane J. Kirkpatrick's Political Woman, published by Basic Books, and Irene G. Diamond's unpublished dissertation for Princeton University, entitled Women and the State Legislatures: A Macro and Micro Analysis.

The Committee -- Gwendolen M. Carter of Indiana University, James David Barber of Duke University, and Dorothy Buckton James of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, congratulates all three authors on their work, and particularly Ms. Freeman who received the prize Their excellent studies push ahead our knowledge and understanding of the character and role of women's movements and women in electoral politics in the United States, and their relation to public policy."

Brookings Fellow

Office of Research and Development, Employment and Training Administration,

Dept. of Labor. 1978-79

Congressional Fellows Program,

American Political Science Association, 1978-79.

Root-Tilden Scholar,

New York University School of Law, 1979-82.

|

Mary Lepper Award, Citation: On Behalf of the Women's Caucus for Political Science The Mary Lepper Award Committee is delighted to present The Mary Lepper Award - 1993 to Jo Freeman whose blend of political activism and scholarship typifies the spirit of Mary Lepper. Ms. Freeman worked in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, was a founder of the Women's Liberation Movement and active in it for many years and is currently involved in Brooklyn politics. Her scholarship revolutionized the study of women and politics. Currently she is working on a book on women and political parties. |

Citation:

It is my very great honor to be here today and I thank NOW for this privilege. Being asked by NOW to present this award today is important to me -- because it validates my credentials as a feminist. And I am grateful.

I am presenting this award to Jo Freeman - who surely has earned it. Jo is a true feminist. Not only does she believe in our ideals -- but also she has made the examination of feminism her life's work.

Jo Freeman is a scholar, lawyer, activist and feminist. You name what has happened in the woman's movement and Jo was somehow there.

-

She was one of the first people to recognize the need for a women's movement.

-

She went to the South for the Freedom Marches.

-

She was a part of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement.

-

She led the troops at the American Political Science Association to move their convention from Chicago because Illinois hadn't ratified the ERA.

-

You name the fight - Jo was somehow always there.

-

Her life parallels the women's movement - she came of age with it.

-

Jo has put her energy and her money where her mouth has been.

-

Jo Freeman is special. She was an early theorist and an early activist in the women's movement.

Jo has a newly published book - it is called A Room at a Time and it is about how women entered party politics - party politics - you know - Democrats and Republicans - political clubs and the like. And she makes a convincing argument that the Republicans welcomed women first.

Yes, we pay homage to her here as a feminist - but Jo is very skilled in the nuts and bolts of day to day political life.

I have a vivid picture of Jo in my mind; a snapshot of her in my memory. Where was she? She was standing in the back of a Brooklyn political clubhouse. You know -- the back near the door. She was counting. Why was she counting? Because she had helped - maybe it was her idea - to pack the club. I was one of the pakees. Jo understands how political clubs work.

Her book, "The Politics of Women's Liberation" published in 1975, won an award from the American Political Science Association as the best book on women published in that year. It is a contemporaneous account and analysis of those events that changed the course of history.

Not only was Jo participating in these events, but she was running home and writing it up. Thanks to Jo these events have not been lost to history - the way so much women's history has been.

From her graduate days at the University of Chicago in the late 60's and early 70's - where her apartment became a center for feminist activity in the Chicago area, she has been an organizer, theorist and historian of the women's movement.

Jo Freeman is well deserving of this honor.

Poilitical Guru Award for the JoFreeman.com website

2001-2002

Citation:

Congratulations on being awarded the Political Guru award. Many sites are submitted, but only a few qualify as being a top political site.

We enjoyed your excellent resources! Some of the things your site was judged on were content, graphics, ease of navigation, and technical skill.

Trey Ragsdale for Pure Politics.com

Leon Epstein Award for Book of Distinction- August 29, 2003

This award was given by the section on Political Organizations and Parties of the American Political Science Association at its annual convention in late August of 2003. It honors a recently published book that makes an outstanding contribution to research and scholarship on political organizations and parties. The text of the award follows:

"Jo Freeman's A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics provides a detailed and engaging history of "party women," a term she uses to describe those women who were involved in party organizations and helped build party support in the electorate in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Unlike more familiar female political activists, such as temperance reformers and suffragists, these women had as their primary ambition to work through the party apparatus and operate to the benefit of the parties.

One of the primary contributions of this historical study is the way it illustrates that parties, as organizations, can shape the activists that lend them service. In the case of party women, the parties gave them room to participate in ways that ensured both that the party apparatus was maintained, and that the party could compete electorally. In addition, Freeman makes a distinction between two routes through which women became influential in the parties: the individual route and the organized bloc route. The organized route was not an especially effective one for women because it required a "group consciousness" that was not encouraged by the party. Instead, individual women, who were either from political families or who had useful experience in non-political clubs, often had male sponsors who encouraged their involvement in the parties. These women were welcomed and seen as useful precisely because they were non-threatening; they were loyal to the party rather than to a cause. Yet despite the constraints placed on them by the male-dominated party organizations, the party women brought a different perspective to the political arena on a variety of issues and paved the way for the eventual acceptance of women as full participants in the political process. A Room at a Time demonstrates the numerous ways in which party women made distinctive and important contributions to the character and history of the political parties."

The Epstein Award Committee for 2003 consisted of Marie Hojnacki, Penn State University (Committee Chair); Alan Abramowitz, Emory University; John Bruce, University of Mississippi; Alan Ware, Worcester College, Oxford.

Keynote speaker at the May 21, 2004 graduation ceremony for Political Science majors at her alma mater, the University of California at Berkeley.

The Price of Democracy

"Democracy" has been much in the news in the last year, as we've gone off, once again, to make the world safe for democracy, whether it wants us to, or not. Yet what we think of as democracy today, is not the democracy of a century ago, or two centuries ago.

The ancient Greeks would not have recognized our form of democracy, and the founding fathers did not intend it. In The Federalist Papers, which all of you read in order to get here today, democracy is defined as something akin to a town meeting, which of necessity was geographically and numerically limited. The idea that political rights should be equal, even among citizens, was alien to its authors. Indeed, in the government they created, very few people could vote and the female half of the population was expected to be silent in public.

Democracy as we know it has evolved through conflict and struggle. Indeed, the essential task of democracy is the civilizing of conflict; not suppressing it and not letting it run wild, but channeling conflict so that its constructive aspects outweigh its destructive ones.

As a result of this civilizing process, tactics once considered threatening are now taken for granted as part of the democratic repertoire.

In seventeenth and eighteenth century Britain, protestors committed civil disobedience through the illegal and disorderly device of political pamphleteering. In the nineteenth century, workers with grievances illegally walked off the job. Today, the "criminal libel" of political pamphleteering is now enshrined as freedom of the press, and the "criminal conspiracy" of striking is now a respected right of labor.

The struggle for democracy never ends because whoever is in power, no matter how benevolent, always prefers order to disorder, inevitably views disruption as a distraction.

In 1941, when A. Philip Randolph threatened a massive march on Washington to protest job discrimination in defense industries and the military, President Roosevelt tried to prevent it. Fearing embarrassment he killed the march by signing an Executive Order stating that defense industries would not discriminate on the basis of race. Twenty-two years later Randolph once again proposed a march, to put pressure on Congress to pass a civil rights bill. President Kennedy argued that this would be counterproductive and that violence might result. But he bowed to the inevitable. The 250,000 people who gathered on the Mall on August 28, 1963 became an historic moment. Since then marching on Washington has become a tradition. Only last month I participated in the largest march in Washington in US history.

Precisely because the extraordinary can quickly become the ordinary, there is a constant search for new tactics, new forms of attracting attention to grievances. However creative these might be, they are never welcomed.

In the 1960s when hundreds of us were arrested for sitting-in, we were denounced by virtually everyone in authority for breaking the law. Today, sitting-in is almost a rite of passage for many. At the 1992 Democratic Convention in New York City I joined several hundred others in an illegal march across the Brooklyn Bridge, followed by a short sit-down which blocked the roadway on the Manhattan side. Among those sitting down (none of whom were arrested) was Robert Abrams, attorney general of New York state, and Elizabeth Holtzman, formerly District Attorney of Kings County.

Yet struggle does not always mean expansion of rights or legitimation of tactics. Barely a hundred years ago, a majority of voters in several Southern states amended their state constitutions in order to deprive a minority -- the descendants of slaves -- of the right to vote. Most of the voting laws passed in other states in those years, with the more laudable intention of curbing corruption, also discouraged people from voting. The lowest turnout for a Presidential election in our history was in 1924.

Movements for expansion and for suppression have fought each other throughout our history. Suppression often finds favor when there is a perception of an external threat. The Patriot Act and the Total Information Awareness project are hardly unprecedented.

During the Red Scare of the 1920s and 1930s, and the Cold War of the 1940s and 1950s, fear of the Communist menace was used to silence dissent and to suppress rights far beyond any realistic need for national security. These rights did not automatically return as the threat receded. The rights lost to fear had to be fought for and regained years later.

When I arrived at Berkeley in the fall of 1961 the University had a Speaker Ban. It was called the Communist Speaker Ban, but was applied to keep off campus any potential speaker who might be deemed controversial, regardless of his or her ideological leanings. In order to keep the University out of politics, politics had to be kept out of the University, or so we were told. Consequently students were not allowed to do anything political on campus, such as hold membership meetings of the University Young Democrats and Young Republicans, or rally in support of any political issue, including local matters affecting students such as a proposed Berkeley fair housing ordinance.

Neither restriction went quietly. The Speaker Ban was an issue in the 1962 gubernatorial campaign; candidate Richard Nixon declared that it should be tightened. After Pat Brown was re-elected, the Regents abolished the Ban. They were inundated with letters from the public who thought that allowing such scurrilous speakers would tarnish the good name and dilute the respect due the University. One dissenting Regent insisted that allowing Communists on campus was like allowing Satan into the pulpit.

The ban on political advocacy by student groups did not go until Berkeley students made international headlines during the Berkeley Free Speech Movement in the fall of 1964. Several thousand of us held a police car hostage for 32 hours in Sproul Plaza; hundreds occupied Sproul Hall four times over two months; 773 were arrested in the last of these sit-ins.

What the Berkeley Free Speech Movement wanted, what created all this furor, was stated succinctly by President George W. Bush in his second state of the union address when he declared that in America free speech is a non-negotiable demand.

This change in attitude is welcome. But other changes came as well that are more problematical. There has been a slow withdrawal of Americans from many of the essential tasks of democracy. Voting declined steadily from a high in the Presidential election of 1960 almost to the 1924 low, in the election of 1996.

Participation in voluntary associations and trade unions has also dropped significantly, even as the number of associations has grown. The new organizations rely on professional staff to pursue their goals, wanting from their "members" little more than writing checks. We are marching more, and meeting less.

This is also true of political campaigns. Money to pay for professional services has replaced time donated by volunteers. The volunteer groups which are the building blocks of civil society are more likely to be run by professionals than by members. Participation by proxy has become the norm.

This norm needs to be challenged, and it is your job to challenge it. If the price of liberty is eternal vigilance, the price of democracy is eternal participation.

In the evolution of democracy, each generation has its own task. The task of my generation was to restore the right to dissent without retaliation. The task of your generation is to recapture the reality of direct, personal participation in civic affairs. As you leave today, degrees in hand, never forget that you are not just political scientists, but political activists, who must make it your personal responsibility to participate in the continuing, evolving, struggle for democracy.

Actual Bush quote from the January 2002 State of the Union Address:

"America will always stand firm for the non-negotiable demands of human dignity: the rule of law; limits on the power of the state; respect for women; private property; free speech; equal justice; and religious tolerance."

Alumnus of the Week, September 20 - 27, 2004

California Alumni Association

Jo Freeman is a well-known feminist scholar, speaker, author and activist. She has published ten books, as well as numerous articles for scholarly and popular journals. At Berkeley in the Sixties: Education of an Activist, 1961-1965, Freeman’s recent accomplishment, is a history and memoir of being a student at Berkeley in the early 1960's. While at Cal, she became deeply involved in the student political groups and immersed herself in the Bay Area Civil Rights Movement.

Freeman has a B.A. in Political Science from University of California, Berkeley (1965), a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Chicago (1973) and a J.D. from New York University School of Law (1982).

Books by Jo | What's New | About Jo | Photos | Political Buttons

Home | Search | Links | Contact Jo | Articles by Jo