What Happened at Berkeley: How the Cold War Culture of Anti-Communism Shaped Protest in the Sixties

To learn more about Jo's book At Berkeley in the Sixties, please go HERE

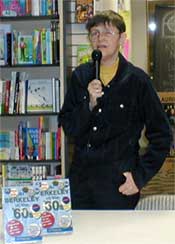

A shorter version of this piece was given as a talk several times during the Spring of 2004. Since it was written as a talk, there are no source citations. These are in the book At Berkeley in the Sixties: Education of an Activist, 1961-1965.

The story of Berkeley in the Sixties begins in the 1930s. During that decade the fear of Communism and the culture of anti-Communism it led to created the conditions for social protest three decades later. The 1930s was the heyday of the Communist Party, the one decade in which its public activities were extensive. Although the campus was not important to the Party, students often formed clubs which were Communist led or inspired. These supported labor strikes and turned thousands of students out for anti-war demonstrations.

The pivotal event in California was the San Francisco general strike of 1934, which badly scared the Regents of the University of California. To appease the Regents and reassure the legislature that the University was in safe hands, President Robert Gordon Sproul issued some new regulations. These regulations limited on-campus speakers to persons approved by the administration, and prohibited "exploitation" of the University’s prestige by unqualified persons. Sproul asked a young campus police officer, William Wadman, to keep his eye on student radical groups and work with other police departments to identify and control subversives.

Although aimed at Communists, over time the application of these rules expanded past its original target. By the time I arrived at Cal in 1961 students were not allowed to do anything political on campus, such as hold membership meetings of the University Young Democrats and Young Republicans, or rally in support of any political issue, including local matters affecting students such as a proposed Berkeley fair housing ordinance. Student groups could sponsor speakers on campus only with the approval of the administration. The Communist speaker ban had expanded to include anyone deemed controversial, including Malcolm X, Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling, and socialist members of the British Parliament. Candidates for public office, including Adlai Stevenson and Richard Nixon, stood in city streets to address students gathered on campus.

The state legislature contributed to the culture of anti-Communism by creating an Un-American Activities Committee. Initially formed by Assemblyman Sam Yorty in 1940, it was reorganized by Assemblyman Jack Tenney in 1941 and followed him to the Senate in 1942. Both men were former leftists from Los Angeles who became virulent anti-Communists. Declaring that "tolerance [of Communists] is treason," Tenney started a battle with the University of California that lasted for thirty years. In 1949 Tenney introduced thirteen bills to ferret out subversives, including a state Constitutional amendment to "give the legislature power to insure the loyalty of officers and employees of the University." This led to a loyalty oath crisis; twenty percent of the faculty refused to sign and 31 professors were dismissed. By the time the crisis was resolved in 1952, faculty confidence in the Administration was badly shaken.

When Tenney went after mainstream politicians he was forced out of his committee. It was taken over by Sen. Hugh Burns of Fresno, but actually run by its counsel, Richard Ellis Combs from his home in a rural county. In 1957, Burns became the first Democrat since 1889 to be elected Senate President pro Tempore. Combs stayed in Tulare Co., where he directed a network of informants who contributed information for his voluminous files on subversives and from where he wrote the Committee’s biennial reports.

As students, we were pretty much oblivious to this legislative scrutiny, but the administration was not. In 1952 Professor Clark Kerr became the first Chancellor at Berkeley; previously President Sproul had been the chief campus officer as well as head of the entire University system. A year later, when Burns asked all California institutions of higher education to appoint liaisons to his Un-American Activities Committee, Sproul asked Kerr to take on that job at Berkeley. Kerr was supposed to supply Combs with the names of all prospective hires to see if they were in the "subversive" files, but he chose to ignore the Committee. His refusal incurred the displeasure of Burns and Combs. Shortly after he was inaugurated as UC’s twelfth President in September 1958, Combs held a secret meeting in his home of subversive specialists in law enforcement and asked them to gather information on Kerr that could be used to undermine and possibly remove him. One of the men at that meeting was the University "security" officer, William Wadman. During the 1950s Wadman had been the chief campus informant to Combs and to the FBI. Once Kerr was President, he moved Wadman off campus and overloaded him with insurance work. Burns and Combs increased their efforts to get Kerr fired.

Scholars often dispute when the Sixties began. In California the Sixties began in 1960. The two pivotal events for California students were the anti-segregation sit-ins begun by students in Greensboro, North Carolina in February, and the anti-HUAC protests in San Francisco in May. Bay area students mounted sympathy pickets in response to the first, and turned out by the thousands for the second. These were not the first student protests, nor the only issues of concern that year, but they were a vast escalation over what had gone before. They highlight what were the two chief concerns of the student movement before 1965: civil rights and civil liberties.

Amidst the silent generation of the 1950s, a new political conscious was slowly emerging. In 1957-58 a few dozen Berkeley students who wanted to discuss off-campus issues on campus formed an organization called SLATE. Its purpose was to run a slate of candidates for student government on a platform supporting civil rights in the South, opposing apartheid in South Africa and abolishing compulsory military training for male students, along with other "political" issues the student government was not allowed to talk about.

SLATE was a constant threat to the existing student government and an irritant to the campus administration. It held illegal rallies on campus on prohibited issues; called itself a campus political party even though it was told it could not do so; challenged the fraternities right to restrict membership on the basis of race; tried to get around the prohibition against Communist speakers by playing tapes of speeches of people who were not allow to speak in person; picketed President Kennedy when he spoke at Cal’s Charter Day ceremonies in 1962; published a review of courses (known as the SLATE Supplement to the General Catalog) that critiqued Cal’s academic offerings; and generally tried to educate students on and off campus ABOUT political issues and mobilize them for off campus actions.

During the early years of the cold war the culture of anti-Communism flourished in California. The search for subversives occupied the time and talents of many amateurs and some professionals. Concentrated in Orange County, it reached even into the liberal Bay Area. At least one Cal student found his vocation as a professional anti-Communist. He founded Students Associated Against Totalitarianism and produced a monthly newsletter called Tocsin to expose Communist sympathizers in the Bay Area. When he left grad school his organization quickly died but his newsletter continued for several more years.

By 1960 some respectable people, such as California Congressman James Roosevelt, were denouncing the destructive effects of Communist hunting, at least by the government. When an 18-year-old Cal sophomore was subpoenaed in April to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) at hearings in San Francisco in May, his colleagues in SLATE were able to mobilize students from Berkeley and other Bay Area schools to picket the hearings. Adverse newspaper coverage of student disruptions brought hundreds more the following day. When refused admittance to the hearings, the students sat down in front of the door of the hearing room. The police turned on the fire hydrants and washed them down the marble steps of City Hall; 64 were arrested. On the third day the students were joined by several thousand longshoremen. HUAC left town and the Mayor said it would not be back.

HUAC saw enormous propaganda value in the student protests and subpoenaed television film of the demonstrations. The resulting film, Operation Abolition, was made part of HUAC’s official report and shown to millions all over the country. Juxtaposing clips of protesting students next to Communists who had been subpoenaed by the Committee, the film said the demonstrations were Communist led and inspired. Operation Abolition put Berkeley on the map as the protest capital of the country; for years to come it attracted politically conscious students to come to where the action was. Both the campus administration and the University Regents were appalled at the film, but Cal students could only see and discuss it off campus. Even faculty members were not allowed to show and discuss the film within the campus borders.

The anti-HUAC protests magnified the importance of SLATE in the eyes of the country’s guardians against subversion. Wadman had reported SLATE’s founding to the FBI, but dismissed it as not a viable organization. When SLATE produced and sold Sounds of Protest, a record of the anti-HUAC demonstration, FBI interest revived. It sent agents to all of SLATE’s summer conferences to gather information and collected its publications, including its reviews of Cal courses. Appended to the FBI reports on SLATE were lengthy descriptions of numerous other organizations that were on its subversive list, some of which weren't even in Berkeley. The California Un-American Activities Committee found the mere existence of SLATE to be evidence of subversion at Cal. The 1961 Report of the Senate Fact-Finding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities issued by the Burns Committee mentioned SLATE 30 times in the 67 pages on Cal. The report made headlines all over the state.

SLATE compounded its sins in March of 1961 when it sponsored a campus speech by Frank Wilkinson, who had been sentenced to a year in jail for contempt of Congress after he refused to answer HUAC’s questions. An accused Communist but not a proven one, Wilkinson was touring the country before serving his sentence. Berkeley’s Republican Assemblyman strenuously objected to the appearance at Cal of an accused subversive; when Kerr refused to cancel the speech the Assemblyman appealed to the FBI. Three dozen carloads of Bay Area citizens personally demanded that Governor Brown deny Wilkinson a university platform. The publicity swelled Wilkinson’s audience to 3,500. The Burns report said his campus talk was one more "capitulation" to the "radical Left" by "the administration of President Clark Kerr".

Kerr had never liked the speaker ban and by 1962 he thought there was sufficient support among the Regents to eliminate it. Governor Brown asked him to wait until after the election because he thought it would be used by his opponent, Richard M. Nixon. Nixon did just that, stating that he would expand the ban to include those who refused to testify before a legislative committee. Knowing none of this, SLATE began a "ban the ban" campaign the following Spring, and was very pleased when the Regents abolished the speaker ban on June 21, 1963. SLATE’s joy was not shared by the thousands who inundated the Regents with letters in opposition. One Regent wrote a long letter in which he said it was "irresponsible" to allow Communist speakers to "tarnish the good name" of the University. In the next six months SLATE sponsored four previously unacceptable speakers: two open Communists, Malcolm X, and a representative of the American Nazi Party.

I joined SLATE early in 1963, previously I’d only been active in the Young Democrats. That was the year that the civil rights movement moved north, and moved to the top of the activist agenda. During 1963 almost one thousand civil rights demonstrations occurred in at least 115 cities, more than twenty thousand people were arrested, ten persons were killed and there were 35 bombings. We began the year trying to prevent the repeal of the Berkeley fair housing ordinance, which was passed by the City Council in January and repealed by the voters in April. While licking our wounds, the Southern Civil Rights Movement grabbed the headlines again, with dogs and fire hoses used against children in Birmingham, Alabama, the assassination of Medgar Evers in June, the March on Washington in August, the Birmingham church bombing in September, and much more.

In the fall the civil rights movement was reborn in the Bay Area. The most militant of the organizations was the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination, which closed down Mel's Drive-In, one of whose owners was running for Mayor of San Francisco. At the core of the Ad Hoc Committee were the DuBois Clubs, which called themselves Marxist Study Groups, but which most of us understood to be the youth wing of the Communist Party. The chief organizer was a Berkeley alum and former SLATE chairman; the chief spokesperson was an 18-year-old girl who had left San Francisco State after one semester to become a full time civil rights activist; the chief negotiator and behind the scenes strategist was an attorney and former President of the S.F. chapter of the NAACP. Most of the warm bodies for demonstrations came from local colleges, especially Cal and S.F. State. After several sit-ins and a few dozen arrests, Mel’s signed an agreement to hire more blacks, and its co-owner lost the election.

This was the first of a series of demonstrations which shook the Bay Area for the next year. CORE and the NAACP took the lead in different demonstrations. Thousands took part in the pickets and sit-ins, most of them students. Approximately 500 people were arrested over six months; some more than once. I was arrested in March and April; one of over a hundred Berkeley students to go to jail for civil rights that Spring. In all of these demonstrations the issue was hiring; the demand was not merely a cessation of discrimination but what we would now call affirmative action. The new Mayor of San Francisco negotiated agreements to end some of the demonstrations; the California Fair Employment Practices Commission negotiated others; some ended without resolution.

We were denounced by virtually everyone in authority, from Governor Brown on down. Berkeley’s Assemblyman demanded that any Cal student arrested more than once should be automatically expelled. The fact that most of us were white was put forth as proof that we didn’t speak for and weren’t supported by the black community, even though our leaders and negotiators were black. One of our negotiators served as the Mayor of San Francisco from 1996 to 2000. One of those arrested became the District Attorney of San Francisco those same years.

The court system was tied up for the next six months while we were tried in groups of ten to fifteen. Although prosecutors challenged every black juror and those with a college degree, there were many still hung juries and about half of us were acquitted. I was acquitted for my first arrest, and sentenced to 15 days and $29 dollars for my second. Leaders were treated more harshly. The young spokeswoman for the Ad Hoc Committee was the only one convicted in her trial group; she got three months in jail. The president of the NAACP chapter, a professor of Pharmacology at the UC Medical School, had one hung jury before being convicted; he was sentenced to nine months of which he served 30 days before Gov. Brown commuted his sentence.

After the March demonstrations the FBI planted a story with a local reporter who wrote that "By actual count, 91 of 167 persons arrested already were known to intelligence agents as party members or party adherents and sympathetic to party causes." The FBI no doubt did background investigations on all those who were arrested. It opened a file on me after my second arrest, sending agents to schools I had attended to find out if there was any derogatory information on me in their files. It also did a background investigation on everyone who went to Mississippi that summer to do voter registration and run Freedom Schools as part of Freedom Summer.

I didn’t go to Mississippi that summer, largely because my second trial took place in July. Instead I hitchhiked to Atlantic City to participate in the vigil outside the Democratic Convention in support of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which was demanding to occupy the seats of the Mississippi delegation.

Meanwhile, back in Berkeley, it was the Republican Convention, in San Francisco’s Cow Palace the same week as my second trial, which was setting the stage for the next phase of the student movement. The city editor of the Oakland Tribune, which supported Barry Goldwater, heard that students were being recruited on University property by the campus DuBois Club to support one of his more liberal opponents, William Scranton. The recruiters turned out to the California College Republicans, but they were doing it from University property. At the southern entrance to the campus was a small plaza, separated from the campus proper by four pillars. It looked like it was city property, and only a few years earlier when the campus boundary had been moved one block, the Regents had voted to give it to the City of Berkeley so that students could carry out political activities that were not permitted on campus. The transfer never happened but students still put their posters on the pillars, gave out literature from their tables and solicited support for their causes as though the plaza was city property.

Word that the Tribune was asking about political recruiting on University property traveled up the administrative ladder to a vice-chancellor. Although student political groups had been using this space for about four years without incident or complaint, he resolved to put a stop to it. He did not like the student political groups and abhorred SLATE. He was particularly incensed about a diatribe against the quality of Cal education printed in a SLATE publication several weeks earlier that was being distributed from the plaza at the campus edge. He wrote a memo to President Kerr that it was "deceitful, slanderous and incredibly hostile."

Before he wrote this memo, indeed while Kerr was out of the country and the Chancellor was on vacation, the Vice Chancellor insisted that the Dean of Students write all student groups at the beginning of the fall semester telling us that we could no longer "support or advocate off-campus political or social action," on the 26 by 40 foot plaza at the intersection of Bancroft and Telegraph. Knowing that eviction from this plaza would significantly cripple our work, we met with the Dean of Students to see if a mutually agreeable solution could be found. She only said that continued use of our space was "almost out of the question." At some point we heard that the Chancellor, now back from vacation, had said that our eviction originated with a call from the Oakland Tribune. Since the Ad Hoc Committee was picketing the Tribune, we just assumed that its owner, a conservative former Senator who had been defeated by Brown for Governor in 1958, had phoned Kerr to object to student picketers, and had probably made some threat that prompted our eviction.

Trained in the tactics of the civil rights movement by the demonstrations of the year before, we put up our tables anyway. Some groups soon moved theirs onto the campus proper. Assistant Deans cited individual students and told them to report to the Dean of Students for discipline. Several hundred of us followed them into the Administration Building (Sproul Hall). We stayed for several hours until the Chancellor announced that eight students had been indefinitely suspended. The next day we put up more tables. This time the campus police chief arrested an alumnus, who was now a full time civil rights activist, sitting behind the CORE table, after he refused to give his name or show identification. When a police car drove onto the large plaza in front of the Administration Building thousands of students sat down around it before Jack Weinberg could be carried to it.

The police car became a podium, and for the next 32 hours students talked, harangued, and debated from its roof. The most eloquent speaker was Mario Savio, who soon became our spokesman and de facto leader. Mario Savio had come to Cal as a junior in the fall of 1963. Born and raised in Queens, New York by devout Catholic parents who wanted him to become a priest, he had an acute sense of right and wrong. Even after he left the Church, Mario believed that it was his Christian duty to resist evil. During the previous fall he had slowly become involved in the Civil Rights Movement and had been arrested at one of the Spring demonstrations. He was acquitted, and his trial ended in time for him to go to Mississippi. For Mario, Freedom Summer was a transforming experience. When he returned he was a man on a mission; the administrations’ refusal to let students do politics on campus became his cause. He saw our eviction as a direct attack on the civil rights movement because it was recruitment for civil rights demonstrations that had apparently led to our eviction from the campus edge. He articulated best the views shared by thousands of us.

We were there all night while the Administration tried to decide what to do. At the urging of the police they agreed that if we weren’t gone by the following evening, we would be forcibly removed and possibly arrested. However, Governor Brown intervened and ordered Kerr to negotiate with us instead. The resulting Pact of October 2 ended the sit-in around the car in exchange for an administrative trial of the suspended students and a tripartite negotiating committee on use of the campus by student political groups.

The next day representatives of the student groups met and created the Free Speech Movement (FSM) to conduct the negotiations, and, if necessary, resurrect the protests. Over the next month the negotiators — students, faculty and administrators -- agreed that student political groups could be active on campus, with access to university facilities that had been prohibited for over thirty years. The sticking point was that students could not advocate on campus activity that was illegal off-campus. Believing that this would limit their ability to recruit students for civil rights demonstrations that might result in civil disobedience, the FSM denounced the negotiations and set up tables on campus. Kerr dissolved the negotiating committee, and the FSM called for another sit-in.

This sit in was a failure; a few hundred students entered the administration building, agonized over why they were there for a few hours, and left. They returned ten days later, after the administration cited four students for violating the old rules back in September. This time over a thousand took over the building, determined to stay. Governor Brown consulted with several people, and told the police to clear the building. I was one of 773 who were arrested that night.

While most members of the public supported Governor Brown’s action, the faculty were outraged and the liberal wing of the Democratic party sided with the students. Arresting students for demanding free speech on campus just did not sit well with civil libertarians. The overwhelming faculty support vindicated the students’ demands; at their December meeting the Regents expressed "devotion to the 1st and 14th Amendments to the Constitution" but demanded preservation of "law and order." Beginning in January, student groups could legally advocate, meet and recruit on campus.

Needless to say, during the fall turmoil, both the FBI and the Burns Committee scrambled to find out who we were. Both started from the assumption that we were mere pawns of some nefarious, behind-the-scenes mastermind, most likely the Communist Party. FBI Field agents initially thought that the FSM "was heavily influenced, if not at times controlled, by individuals who were members of or affiliated with subversive organizations," but they eventually realized that there were barely a "handful" involved. Nonetheless, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover testified before the House Appropriations subcommittee on March 14, 1965 that there were 43 persons with "subversive backgrounds" in the FSM, including five faculty members. He said the Communist Party had exploited the FSM.

The FBI had already done a background check on Mario as it had on all the Freedom Summer volunteers, but it now sent investigators to his former schools to find out everything it could about him. Field agents found no indication that he was a subversive, but were bothered that one of his close associates in the FSM was Bettina Aptheker, who was the daughter of a prominent Communist. Deeply offended by Mario’s "contemptuous attitude" toward our government, the FBI kept him under surveillance at least until 1975. Agents regularly phoned his parents under the pretext of being an old friend and talked to neighbors who might know him. The FBI regularly sent information on his whereabouts to the Secret Service, checking box 3, for "potentially dangerous." In 1968 it identified him as one of three "Key Activists" of the New Left in San Francisco and thus subject to the "new Bureau counterintelligence program."

The 1965 Burns Committee report was devoted to the Berkeley student revolt. To support its thesis of outside control it contained detailed descriptions of meetings and conventions all over the country of allegedly Communist groups. These explained "why the Berkeley Campus was selected as a target for the mass demonstrations that started in September 1964." It was full of factual errors and heavily seeded with names of people I had never heard of, let alone seen at an FSM meeting. The one person over thirty whose opinions were attended to by the FSM militants was named only in the Bibliography. Much more than the FBI reports, the Burns Committee report was completely oblivious to what was really going on. Instead it connected every dot it could find, or make up, to put all the blame on Clark Kerr. It said Kerr was so easily taken advantage of by the Communist-led FSM because he was soft on Communism and always had been.

Kerr challenged the report, and even asked Burns to waive legislative immunity so he could be sued for libel. Some Regents who had never liked Kerr tried to use this report to have him fired, but Governor Brown was solid in his support. A few months later Kerr released his own analysis, documenting the inaccuracies of the Burns report. The following May, the Burns Committee issued a Supplement attacking Kerr even more vehemently than it had the year before (and stating that statutory immunity was not subject to waiver). Although the Regents stepped in to put a stop to the confrontation, by then what happened at Berkeley had become an election issue. It helped Ronald Reagan defeat Governor Brown’s re-election. At the first meeting of the Regents after Reagan’s election, Kerr was fired.

The impact of the Burns report didn't stop at the California borders and it wasn't confined to the prominent and the powerful. After graudating in 1965, I went South to do voter registration for SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference). The Burns Committee report followed me. I had four honorable mentions in the 1965 Report, all innocuous, three of which were true. Someone pasted those four paragraphs onto a page with other excerpts on "Communists in the Rebellion." Titled "MISS JO FREEMAN, WHITE FEMALE PROFESSIONAL COMMUNIST AGITATOR," it was circulated in some of the small Alabama towns in which I worked.

That particular piece of paper didn't surface in SCLC's voter registration project in Grenada Mississippi in the summer of 1966. Instead, on August 18, 1966, the Jackson Daily News, which called itself "Mississippi's Greatest Newspaper," exposed me in an editorial headlined "Professional Agitator Hits All Major Trouble Spots." It cited the Burns report as its major source of information, even for things it did not say. It implied that I was a Communist, though it didn't specifically say so (which would have been libel per se). The editorial was accompanied by five photographs, including one taken on December 3, 1964 of my speaking from the second floor balcony of the administration building. As soon as my boss, Hosea Williams, saw that editorial he put me on a bus back to Atlanta. "That thing makes you Klan bait," he said. "We don't need more martyrs right now."

For years I assumed the FBI was behind this story. It had all the earmarks of an FBI plant, requiring connections between California and Mississippi. My belief was reinforced when the FBI's Cointelpro actions against the Civil Rights Movement in general and its persecution of Dr. Martin Luther King in particular were revealed. Not until 1997 did I discover that the actual source of the editorial and photos was the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission (MSC), an official state agency of which I was completely unaware in 1966. And only after reading many pages in the MSC files at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History did I realize that I and others like me were not just foot soldiers in the civil rights movement, but cannon fodder in the Cold War.

After years of litigation by the ACLU, in 1994 a federal court ordered Mississippi to open the MSC files and notify "victims" through public advertisements that we could obtain copies. When I got the pages on which my name appeared I discovered that the MSC had its own spy on the Berkeley campus. Edgar Downing, a welder from Long Beach who grew up in Mississippi, took photos of me and many others and sold them to the state of Mississippi for its own extensive files.

Mississippi's interest in California was sparked by the Berkeley students who had participated in Freedom Summer a couple months before the FSM. Mario Savio had worked in McComb, Downing's home town, for a few weeks. SCLC's summer 1966 Grenada project brought Downing back to Mississippi, where he took more photos and sold them to Erle Johnston, Jr., Director of the MSC. Johnston, who had been a professional publicist before joining the MSC, wrote the editorial and arranged for the Jackson Daily News to publish it and the photos which made me "Klan bait."

Although full of falsehoods and innuendos, the newspaper published the editorial as true, even though HUAC's Chairman responded to a query from a Mississippi Congressman that there was no record of my having had an "association with officially cited Communist or Communist-front organizations." Why did it do so? Because the culture of anti-Communism permeated the South. Implying that civil rights workers were Communists associated two evils with each other and reinforced Southern beliefs that "outside agitators" were a foreign as well as a domestic threat.

The Jackson office of the FBI clipped the page from the newspaper and sent it to Headquarters. This began a feedback loop. Reports from the Jackson FBI office state that (name blacked out) contacted them, and identified JO FREEMAN as a demonstrator in Grenada, Miss. "(__) who has furnished reliable information in the past, advised that FREEMAN is .... also listed by the Un-American Activities Committee of California as a subversive." The charge that California thought I was a subversive shows up on several pages in my personal FBI file, even though the San Francisco FBI office repeatedly says that "No subversive activity is known." The Burns report didn't that say I was a subversive, though it included me on SLATE and FSM lists. I realize that to the State of Mississippi all civil rights workers were subversives, but it is California that is credited with my designation as such. Mere mention in the Burns Committee report was enough.

It did not matter if you were a powerful President of a major University, or a foot soldier doing voter registration, once you were labeled by the anti-Communist culture as a subversive, or a possible subversive, or someone who might participate in activities which other possible subversives also participated in, you were labeled forever, without even knowing it.

For all this money spent on investigation and time spent exposing ordinary Americans with dissenting views, did these agencies discover any threats to our national security? From the files I've seen, they knew less about what was going on at the Berkeley campus than ordinary students and faculty who read the student newspaper. The FBI files and the SUAC (Senate Fact-Finding Subcommittee on UnAmerican Activities) reports are full of errors. They identify as possible nefarious influences people we did not know, or know of, and don't identify the ones we did know. This was not just a matter of bad reporting. When agents in the field discounted Communist control, those at the top told them they weren’t looking in the right place. The SUAC reports give the impression that Combs was living in a fantasy world; he interpreted and reinterpreted every smidgen of information and misinformation to support his world view about the imminent Communist menace and discounted anything that didn't fit. Consequently, both federal and state investigative agencies completely missed what was really going on on campus -- the birth of what came to be known as the New Left. Instead of realizing that something new was happening in the country, the agencies looked for something old and familiar. Those assigned to find the Communists pulling the strings of student protest found what they were looking for, even though it wasn't there.

To Top

Books by Jo | What's New | About Jo |

Photos | Political Buttons Home | Search | Links | Contact Jo | Articles by Jo