| |

|

|

|

Feminism and Antifeminism in the Republican and Democratic Partiesby Jo Freeman: Chapter 10 of her book We Will Be Heard By the end of the twentieth century feminism had become highly identified with the Democratic Party and antifeminism with the Republican Party. This development was neither planned nor predictable. When the women’s liberation movement emerged in the mid 1960s its founders had no desire to become closely identified with any political party; many of them viewed both parties as representatives of a status quo which they disdained and the rest preferred bipartisan activity. Furthermore, the parties with which feminism and antifeminism became identified are the opposite of their historical affiliations. Over a period of thirty years not only did feminism become highly partisan in nature but the parties switched sides. The original identification of feminism with the Republican Party and antifeminism with the Democrats was not a strong polarization. Not only was there much overlap in the party affiliations of both sides, but the antifeminists in the Democratic Party were largely social reformers who had worked with the feminists in pursuit of female suffrage. After ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment they eschewed the label “feminist,” primarily because it was used by the militants of the National Woman’s Party (NWP) with whom they disagreed on the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and protective labor legislation. Although they shared with the antifeminists of today some beliefs, such as a woman’s need for protection due to her lesser physical strength, different emotional makeup, and special responsibilities for the welfare of the family, they never doubted that women were still men’s equals. At its founding in 1916, the NWP had chosen to follow the British example of blaming the party in power for any legislative failures. Woodrow Wilson was a Democrat, and his repeated failure to support Suffrage until circumstances forced him to do otherwise forever tainted the Democratic Party in its eyes. The Congress which sent the Suffrage Amendment to the states for ratification was a Republican Congress and twenty-nine of the first thirty-six states to ratify it had Republican legislatures. In 1928 the NWP even endorsed Herbert Hoover for president despite the fact that he had not personally expressed support for the ERA. His running mate, Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas, was the chief ERA sponsor in the Senate and his Democratic opponent, New York Governor Alfred E. Smith, was an ardent supporter of protective labor legislation. Most Democrats left the NWP as a result (Becker 1981). After almost two decades of struggle, Republican feminists succeeded in getting an endorsement of the ERA into their national party platform in 1940. Democratic feminists didn’t succeed until 1944, and did so then largely because protective labor laws had been suspended when women were needed in wartime industries. ERA opponents remained active in the Democratic Party and replaced the ERA with modified language in the Democratic platform in 1960. The ERA disappeared from the Republican Party platform in 1964 because the party wanted a short platform that year and thus left out issues it considered no longer relevant. Both parties left it out of their 1968 platforms; by then the NWP was so weak it couldn’t muster much support and awareness of gender issues was very low. Indeed the 1968 Democratic Party platform did not so much as mention women, while the Republican Party platform expressed concern for discrimination on the basis of sex (among other things) (Freeman 2000). However, by 1972 the women’s liberation movement had captured public attention and put feminist issues back on the national agenda. Although there was some opposition to the ERA from a few new feminists in the late 1960s, the issue of protective labor legislation was largely mooted by court decisions on the “sex” provision of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The National Organization for Women (NOW), founded in 1966, made passing the ERA a priority. After a two-year campaign, the ERA was sent by Congress to the states on March 22, 1972; it was expected to be ratified quickly. Thus the ERA was not an issue for either the Democratic or the Republican parties that year.

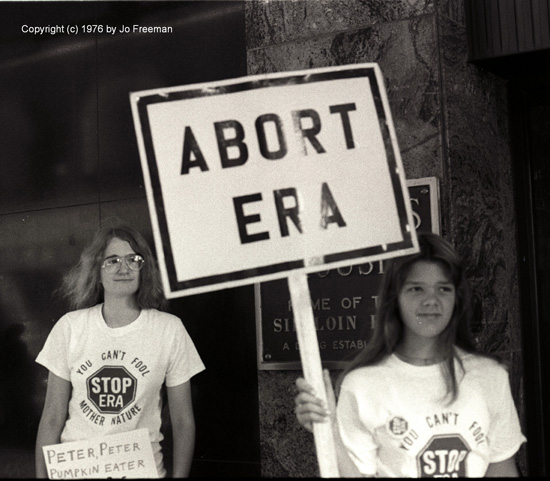

Congressional passage of the ERA and the Supreme Court decision on abortion provoked grassroots movements against each of them. Begun separately, these movements eventually merged as the participants in each sought common cause against feminists, liberals, and seculars. Abortion in particular prompted partisan realignment, as pro-choice and pro-life voters switched to parties that conformed to their views, and candidates often switched views in order to be elected by their parties. The beginning of this switch could be seen at the 1976 conventions, though at that time the primary issue was the ERA. Abortion would rise to prominence in 1980 and stay there; the ERA lost salience once the 1982 deadline for ratification passed. By the 1976 conventions the stage had been set for major battles over women’s issues in both parties, but they were very different battles. In the Democratic Party feminists fought for power independently of other struggles going on within the party. In the Republican Party feminists fought for the ERA as part of the contest between Ronald Reagan and Gerald R. Ford to head the party’s ticket. In the Democratic Party, feminists lost their battle but won the war. Feminists in the Republican Party did the opposite (Freeman 1976a).

In the Democratic Party, keeping the ERA was not an issue, and a compromise was reached on abortion to oppose a proposed constitutional amendment eliminating it. The fight at the 1976 convention was over “50–50”—whether the rules should be amended to require that delegates to the quadrennial nominating conventions be half women. While Democratic women debated at daily meetings of a women’s caucus whether or not to take this issue to the floor of the convention, a compromise was reached between the feminists and the campaign of Jimmy Carter. Carter sensed victory and didn’t want a divisive floor fight. They agreed that 50–50 would not be demanded now, but might in the future (Freeman 1976b). As a result, the rules for the December 1978 midterm convention were changed to require equal division, and at that convention the Democratic National Committee amended the 1980 “call” to also require it. As it had for Democratic women, the political environment for Republican women changed between the 1972 and 1976, but it was a shift to the right. The person most identified with the defeat of the ERA in the states is Phyllis Schlafly, who as late as 1971 did not find it objectionable. However, in February 1972 she devoted an entire issue of her newsletter, the Phyllis Schlafly Report, to condemning the ERA for its detrimental impact on the family. Schlafly had long been active in the right wing of the Republican Party, whose ranks had been augmented in the 1950s when the National Federation of Republican Women expanded its numbers by recruiting many women active in right-wing causes (Rymph 2006). Until the ERA came along, Schlafly’s concerns were primarily in the areas of foreign affairs and military policy. These activities and her publications gave her a wide base among conservative Republicans, which she mobilized against the ERA. The response was strong enough to prompt her to form STOP ERA in October 1972 with herself as chair. Schlafly brought her supporters to the 1976 Republican convention for the purpose of removing the ERA from the platform. She also supported Reagan’s quest for the Republican nomination for president. By 1976 Reagan opposed the ERA (having changed his mind); Ford supported it (and always had). All of the key RWTF members at the 1976 convention were tied to the Ford campaign personally or professionally.

Feeling that Ford’s reelection was the single most important contribution they could make to the women’s movement, the RWTF chose to ignore abortion and possible rules changes in favor of working only to keep the Equal Rights Amendment in the Republican Party platform. Nonetheless, the ERA actually lost in the relevant platform subcommittee by one vote. This so shook up the Ford campaign that they ordered their delegates on the full committee to vote for it. It still won only by 51 to 47. The platform took “a position on abortion that values human life” after a 1:30 a.m. effort to remove all mention of abortion from the platform led by Rep. Millicent Fenwick (R-NJ). In 1980 there was a good deal of tension between feminists and the leaders of both parties. At both conventions feminists had poor relations with the dominant candidate’s campaign, but this resulted in their virtual exclusion from the Republican convention while at the Democratic convention it was merely a stimulus to alternative routes of influence. Most of the Republican feminists who had been active in the 1972 and 1976 conventions did not go to the 1980 convention. Some had received political appointments from the Carter administration and thus were legally prohibited from participating in politics. Others were just discouraged by what they expected to be a hostile atmosphere. The ERA was easily removed from the Republican platform in the subcommittee. The RWTF recruited former RNC chair Mary Louise Smith, whose Republican credentials were too solid to be dismissed, to talk to the Reagan campaign. Consequently, the anti ERA language of the subcommittee was modified to oppose not the ERA itself but federal pressure on the states that had not ratified. A strong statement in support of a Human Life Amendment was put into the platform. By 1980 most feminists who were not personally tied to the Democratic Party were disaffected from it. They blamed the Carter administration for not doing enough to get the ERA ratified and to maintain women’s right to get an abortion. NOW’s Board and PAC had voted to oppose the nomination and reelection of President Jimmy Carter in December 1979, leading the Carter campaign to assume that they were supporting challenger Senator Ted Kennedy. Although NOW was only part of the feminist coalition active at the 1980 Democratic convention, the DNC refused to allot hotel space for the usual women’s caucus meetings. Instead women met at a nearby labor union hall. About 20 percent of Democratic delegates identified themselves as feminists in the first 50–50 convention, giving the feminist coalition a great deal of clout even though they were outsiders. The coalition decided to demand a platform plank that “the Democratic Party shall offer no financial support and technical campaign assistance to candidates who do not support the ERA.” This won in a voice vote on the floor. Another measure added support of government funding for abortions for poor women to the support for the 1973 Supreme Court decision already in the platform. It won overwhelmingly in a floor vote. However, Democratic incumbent Carter lost to Republican challenger Ronald Reagan in November, mooting any possibility of putting these provisions into practice.

By the end of 1980, it was clear that the Democratic Party and the Republican Party were rapidly moving in opposite directions on any issue that could be identified as feminist. Feminists in the Democratic Party had a veto on any platform proposals or candidates for President they did not like, and antifeminists had a similar veto in the Republican Party. For the first time in many years, a significant difference appeared in the way men and women voted in November. Women were 8 percent more likely to vote Democratic, and men were more likely to vote Republican. Because of their veto power, Democratic candidates for President in 1984 went out of their way to court feminists. Jesse Jackson dropped his opposition to abortion so he could be a credible candidate from the Democratic left (Bill Clinton would change his position for 1992). All of the candidates spoke at the NWPC convention in July, and courted NOW after it announced that it would endorse one of them. After NOW endorsed front-runner Walter Mondale his campaign put a NOW vice president on the platform drafting committee with authority to veto any proposal or language that NOW did not like. An incipient women’s caucus, run by the DNC Women’s Division, decided to focus its efforts on persuading Mondale to choose a woman as his running mate. The women put together a short list; Mondale chose New York Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro. After Mondale lost badly to incumbent President Reagan, party insiders blamed the feminist pressure to run a woman for vice president. However, polls showed that Ferraro’s presence really hadn’t made a difference one way or the other. If Mondale had not been so far behind before the conventions were held, he most likely would not have made such a novel choice. Candidates who feel victory is near rarely take risks. It is candidates who feel they have nothing to lose who try to do something different, in hopes that a long shot will pay off in the end. This time, it didn’t. Although the Reagan campaign never felt Mondale was nipping at its heels, the Republican Party did make a special effort to reach out to women. At the convention this influence could be seen not in the content so much as in the quantity of attention paid to women. Although the Republican Party has never required that half of its delegates be women, 48 percent were female in 1984, as were 52 percent of the alternates. One third of the major speakers were women and for the first time the Republican convention had a large booth in the press area solely to provide information on women. Women and women’s issues occupied a larger portion of the platform than ever before, though the content was dictated largely by Phyllis Schlafly and the Moral Majority. When anything was proposed in a platform subcommittee that might appeal to feminists, it was denounced and handily voted down. When Republican feminists tried to speak about their concerns for the platform, they were harshly quizzed about the finances of Ferraro’s husband (Freeman 1985). The RWTF had, for all practical purposes, disbanded. Because the Reagan administration’s attitude toward feminist organizations was that they were extensions of the Democratic Party, many Republican women who were sympathetic to feminist issues would have nothing to do with the NWPC. Instead they formed the Pro-Choice Republicans and joined the Republican Mainstream Committee. These would continue to host events and hold press conferences at Republican conventions for many years, but would never have any power in the national party (Melich 1996).

The activities of feminists at the 1988 Democratic convention were driven by an overriding desire to elect a Democratic administration in November. For feminists, the Reagan administration was a disaster, as the only women he listened to were those who opposed everything they wanted. They swallowed their pride and made no demands. They held their tongues even when Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis chose as his running mate an opponent of federal funding of abortions. But by now feminists were getting pretty much everything else that they wanted. The Democratic platform had feminist planks and feminists had important positions in the campaign. Publicly at least, the parties had completely polarized on feminist issues; the Democratic Party was the feminist party and the Republican Party was the antifeminist party. By the 1992 conventions each party’s positions on women had become institutionalized to the point where they were not seriously questioned within either national party. Party differences were clearly evident to the voting public. Although the party platforms and the speeches at the conventions devoted many words to many issues, each party’s vision can be summed up in a slogan. The Republicans articulated theirs with the phrase “family values.” While their platform did not define this slogan, both the document and the speeches indicated that it stood for programs and policies which strengthen the traditional two parent, patriarchal family in which the husband is the breadwinner, the wife is the caretaker, and children are completely subject to parental authority. The Democrats incorporated into their platform the feminist view that “the personal is political” and put on the public agenda issues which were once deemed to be purely personal. The most controversial of these was abortion; the most recent was sexual harassment. In between were a plethora of concerns ranging from wife abuse and incest, to ending discrimination against gays, lesbians, and others living nontraditional lifestyles, to proposals to reduce the conflict between work and family obligations. Abortion was still the reigning issue. No longer seen as just a “women’s issue,” or even a debatable one, it had become a deep moral conflict on which elections could be won or lost and on which deviation from each party’s official line was tantamount to treason. Democratic convention chair Ann Richards denied the request of the Democratic governor of Pennsylvania, Robert P. Casey, to speak against what he claimed was the platform’s support of “abortion on demand.” She herself set the tone when she began her own opening remarks Monday night by declaring “I’m Pro Choice and I vote.” Virtually every speaker in the four-day marathon pledged fealty to choice and received thunderous applause.

Nonetheless, the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL) and Planned Parenthood lobbied for the Freedom of Choice Act, by which Congress would limit the states’ ability to impose restrictions on abortion. At the Republican convention, Phyllis Schlafly’s STOP-ERA was reincarnated as the Republican National Coalition for Life. Although not a member of the platform committee this time, Schlafly and her minions worked closely with the Bush campaign to “Keep Our Winning Platform,” as their lapel stickers declared. An attempt to remove all language concerning abortion was squashed. The right-wing conservatives were so dominant in so many states that former RNC chair Mary Louise Smith could not be elected a delegate from her home state of Iowa. The ease with which feminists and antifeminists could have their respective positions adopted by the two major parties was facilitated by major transformations within each party. The underlying cause was a change in the social base of each party. Traditionally, the Republican Party had been the party of the middle class and the Democratic Party the party of the working man. Before World War II people with more education were more likely to be Republicans. The GI Bill sent the children of the working class to college, making them part of the educated middle class. They filled the ranks of the ballooning professions, but kept the political faith of their parents. As a result the relationship between party preference and education became curvilinear: the most and the least educated people were more likely to be Democrats while those in the middle were more likely to be Republicans. It was the college-educated children of the working class that led the reform movement in the Democratic Party. This reform movement began in the early 1950s, but blossomed in the 1960s when the civil rights movement illuminated minority underrepresentation. The Democratic Party’s support for civil rights stimulated a racial and regional realignment; by 1980 African Americans had replaced Southern whites as a key Democratic constituency. That year also saw the beginning of the modern-day “gender gap,” as fewer women than men voted for Republican Ronald Reagan. In the six decades before 1980, when there was a national gender gap it was because more women were voting Republican. The Democratic Party has always been a pluralistic party, in which representing an important group entitled one to a say in party policy. The reform movement within the Democratic Party changed the nature of that representation from geographic entities to demographic entities. The party morphed from a coalition of state parties and local machines into one of national constituencies. Organized labor retained its traditional clout, but over time it was joined by organized minority groups, women, gays and lesbians, and others who won acceptance within the party by their ability to elect delegates, raise money, and conduct quadrennial struggles over platform planks and rules changes (Freeman 1986). The Republican Party began in 1854 as the party of progress but soon developed a conservative wing. Dividing on issues of national defense, foreign policy, and economics, the original conservatives were not culturally conservative. Many of those who won the party’s nomination for Goldwater in 1964, including Goldwater himself, were pro-ERA and pro-choice. But these were not priority issues for those conservatives. They were priority issues for evangelicals, especially Southern evangelicals. When the Democrats’ support for civil rights led to white flight, Southern Democrats joined the Republican Party, bringing their conservative cultural values with them. This shift was encouraged by more traditional Republicans in the expectation that the evangelical voters would give the party victory at the polls. In the 1970s several well-known ministers were recruited by hard-right Republicans looking for troops. They in turn persuaded their deeply religious followers to overcome their repugnance to party politics as well as their traditional Democratic voting habits. Politicized by the legalization of abortion, evangelical Christians began to move into the Republican Party in 1980 to support Ronald Reagan. Pat Robertson’s 1988 Presidential campaign organized them to become delegates to the 1988 convention. Not warmly received by more traditional Republicans who found them rather déclassé, their persistence, organization, and numbers compelled their reluctant acceptance. As their numbers and influence inside the GOP grew, they drove out the party’s liberal wing—the political descendants of the original abolitionists and progressives—whose voters clustered in the Northeast. Most of these eventually joined the Democratic Party, or at least voted for Democratic candidates. By 1992, the Christian right had the same hegemony over social issues within the Republican Party that the liberal constituency groups did inside the Democratic Party. They not only wrote the platform, but the party line. ReferencesThis article is heavily based on my coverage of feminist and womens activities at the Democratic and Republican conventions. Ive been to every Democratic convention since 1964 and every Republican convention since 1976. Some of my published stories are cited below. Becker, Susan D. 1981. The origins of the Equal Rights Amendment: American feminism between the wars. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

To Top Books by Jo | What's New | About Jo | Photos | Political Buttons Home | Search | Links | Contact Jo | Articles by Jo

|

|

|